vol. 1

Mono Masters

(1955 to 1958)

vol. 2

Peak Contemporary

(1958 to 1966)

vol. 3

Tone Changes

(1966 to 1984)

vol. 4

Idiosyncrasies of the Sound (1984+)

The seeds of expansion

were planted in 1960, with a wedding gift between ex-spouses. Celia Mingus was remarrying, this time to Fantasy Records executive Saul Zaentz, and ex-hubs Charles Mingus bequeathed the couple something mighty indeed: the Debut Records catalog.⁽¹⁾

Debut was a star-studded but short-lived jazz shingle originally founded by the Minguses and Max Roach in the early 1950s. Fantasy was its contemporary, a west coast shop, similarly jazz-forward with a slightly broader catalog and much whiter roster. Fantasy survived to see the Kennedy administration, though, and proceeded to outplay old competitors by diversifying its roster and riding Creedence Clearwater Revival through the sixties rock scene.

Not content with evolution alone, Fantasy (with Zaentz soon at the helm) grew through acquisition. In the early 1970s, it absorbed jazz crown jewels Prestige and Riverside and kept looking for more.⁽¹⁾ A decade later, Contemporary Records wandered into that very gaze.

For Contemporary, the prior few years had been clouded by a legal standoff between Lester Koenig’s estate and widow Joy Bryan Koenig (the singer who led Contemporary 3604 Make the Man Love Me). Per Billboard, the legal battle had sent Contemporary’s operations into paralysis in its final years.⁽²⁾

The tug of war ultimately wore on John and Victoria Koenig and drove them towards acquisition:

Ultimately, the stress of trying to run an independent jazz record company while at the same time enduring relentless legal attacks from my step-mother caused my sister and me to decide to sell the company and try to get on with our lives.

— John Koenig ⁽³⁾

And so it was, after months of negotiations, that a probate court approved the label’s sale to Fantasy in October 1984.⁽⁴⁾

Fantasy Studios

With rights to the Contemporary and Good Time Jazz master tapes, Fantasy also took ownership of any extant metalwork (as well as any completed inventory⁽⁴⁾). John Koenig’s tenure had facilitated numerous excellent cuttings and left behind (what one would assume was) a significant supply of metal to press from, and while some of that metal was indeed re-used in the earliest tranche of Contemporary OJC titles, it seems that Fantasy scrapped most of it to cut new lacquers themselves.

Those cutting duties fell to Fantasy Studios in Berkeley and a mastering team led by Chief Engineer George Horn.

Original Jazz Classics

(1st gen, 1980-1990s; 2nd gen, 2000s-2010s)

Fantasy rushed Contemporary OJCs to market just before the holiday season in 1984.⁽²⁾ Staring with OJC-151, thirty Contemporary titles were released in unbroken sequence, up through OJC-180. This took the series into 1985, and CR titles would be continually folded into the lineup year after year through 1992.

In the late 1980s, cassettes and CD variants began to appear alongside the LPs, with the smaller formats quickly stealing market share from the phonograph. In the early 1990s, new OJC LP releases ceased completely as CDs continued the product line. Meaning some Contemporary titles were reissued on CD only.

Among the many engineers who worked on Contemporary titles in this 80s-90s era were George Horn, Gary Hobish, Phil DeLancie, Joe Tarantino, and I’m sure several others.

A handful of Fantasy’s more popular titles stayed in print on LP into the 2000s and beyond, which meant most of them needed recutting. Luckily, Fantasy Studios maintained a lacquering facility with George Horn still at the helm.

Sometime after the 2004 merger of Fantasy and Concord, that mastering arm broke off into George Horn Mastering but continued servicing Concord jobs at volume.⁽⁵⁾ One of the engineers who cut numerous Contemporary sides at GHM was Anne-Marie Suenram, her lacquers recognizable by her A·MS initials etched in the runouts. She also notably cut a handful of boxsets for Craft Recordings (2017+), including the 2018 Deluxe Edition of Way Out West.⁽⁶⁾

Full-price Fantasy reissues (non-OJC)

(mid-1980s)

It’s important to note that OJC was Fantasy’s budget series in the 1980s and limited to a certain number of titles over time (even if in hindsight its pace seems breakneck).

Regular (higher) list prices were reserved for standard releases.⁽⁴⁾ This included the most popular Contemporary titles — Way Out West, Art Pepper Meets, My Fair Lady, The Poll Winners — which didn’t get slotted into the OJC lineup for a number of years.

Standard reissues in this period adapted the old Contemporary packaging, so identifying these reissues is a touch more difficult than an OJC.

This is simple enough, mind you, but it requires stepping through deeper identifiers. As so:

Jacket. Generally pre-1984 artwork assets were reused but if a title needed reprinting, the label address across bottom of the liner notes would be replaced with Fantasy’s own. Jacket construction varied a bit but usually followed whatever Koenig-Contemporary had previously done for the title.

In some cases, leftover jacket inventory was sufficient to sustain more pressing runs. So old jackets with the P.O. Box 2628 or 8481 Melrose addresses were sometimes used to house brand new Fantasy pressings. If that’s the case-

Center labels. Fantasy’s Contemporary reissues (both OJC and non-OJC) mimicked the color and outer ring of Contemporary yellow labels, but actual title copy was printed with highly lackadaisical linecasting never seen on anything pre-1984.

Contemporary label design.

Fantasy label design.

We should still consider some inexactitude from date floors and date ceilings and stockable materials. LP labels are indeed a stockable material that could be printed years before being actually used. So some Fantasy reissues reused pre-1984 Contemporary labels.

Which makes things really tough. So we need the third and most definitive identifier…

Runouts. The Fantasy Studios lacquers are obvious because they don’t identify LKL or LKS tape numbers, and they don’t use D numbering for lacquer cuts. Instead these lacquers reflect the release catalog number. For these list-price Fantasy reissues that means S-7500 numbers.

Here’s an example. This copy of Friday Night at the Village Vanguard has a jacket and labels identical to the original from 1980. It’s even pressed at a CBS plant with a 69mm pressing ring, like the original was.

I ordered this copy after carefully checking eBay photos and had no doubt that it was the original John Koenig cut plated at SLM. On receiving the disc, though, I discovered the Fantasy runouts which routinely included catalog number (in this case S-7643) but never used the old LKS tape numbers.

Analogue Productions

& Craft Recordings

Chad Kassem started dealing records under the Acoustic Sounds banner in the mid-1980s, rapidly expanding from a two-bedroom apartment stuffed wall-to-wall with records to a warehouse operation in downtown Salina, Kansas.⁽⁷⁾

From his mail-in dealer business emerged an audiophile reissue label, Analogue Productions, in 1992. Chad was the rare analog ideologue in an increasingly CD world and insisted on a certain quality: he sourced original master tapes, hired the best analog-capable mastering engineers, and contracted the best plating and pressing plants in the world.

To build some pedigree for the label, Chad targeted recordings and labels well known for their sound quality. Contemporary was at the very top of that list.

‘APJ’ LP & CD Reissues

(1992-1994)

AP licensed several Contemporary titles from Fantasy in the early 1990s, starting with Way Out West and Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section. The LPs were cut by Doug Sax directly from the stereo master tapes, using the all-tube system at his Mastering Lab in Hollywood. He also created digital 44/16 masters, which AP pressed on gold CDs.

In this process, Chad drew the attention of John Koenig, who was happy to see Chad taking up the Contemporary tapes but quick to tell him he should have hired Bernie Grundman to master them.⁽⁸⁾

Chad didn’t fire Doug, but he did make some room for Bernie by asking him to master the same two titles for CD. Thus AP ended up releasing parallel sets of Way Out West and Meets the Rhythm Section CDs mastered by the two engineers.

The experiment fell a bit flat, though, leaving little impression on listeners who were not eager to buy multiple versions of the same title.⁽⁸⁾ Chad never repeated the shootout format, for Contemporary or anything else, and in the near term he continued drop shipping Contemporary tapes to The Mastering Lab.

Subsequent reissues of Ben Webster at the Renaissance, Smack Up, and Jazz Giant came in 1993, as well Art Pepper +11 in 1994. All of these, as well as their gold CD counterparts, throw John K. a shoutout for “supporting our efforts to produce the highest quality product possible.”

John also penned a new set of liner notes for Renaissance, it being the first all-analog cut ever released and the first to honor Lester’s preferred sequencing.⁽⁹⁾

“Revival Series” LP Reissues

(c. 1996)

In 1995, Acoustic Sounds partnered with SoCal pressing/plating plant RTI (Record Technology Incorporated) to build AcousTech Mastering inside RTI’s facility. As Chad selected more Contemporary titles for reissue, rather than outsource to another cutting studio, he chose to keep it “in-house” at this co-owned operation.

The cutting engineer hired to man the lathe at AcousTech was Stan Ricker, well-known in the annals of audiophile history as the engineer behind early-gen Mobile Fidelity reissues. Having cut one Contemporary reissue (West Side Story) for Mobile Fidelity back in 1983, his next contact with the label came thirteen years later with the Analogue Productions Revival Series.

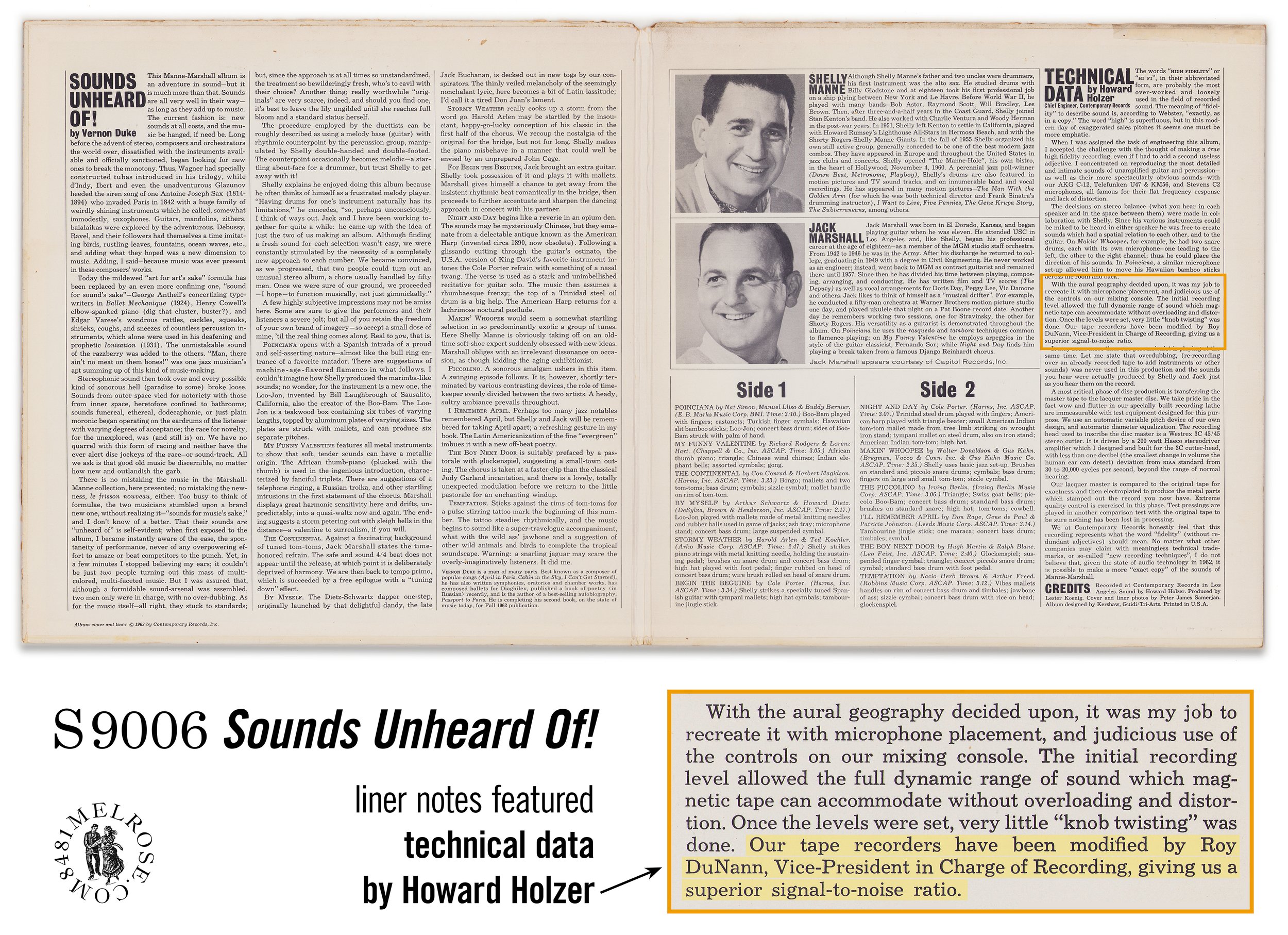

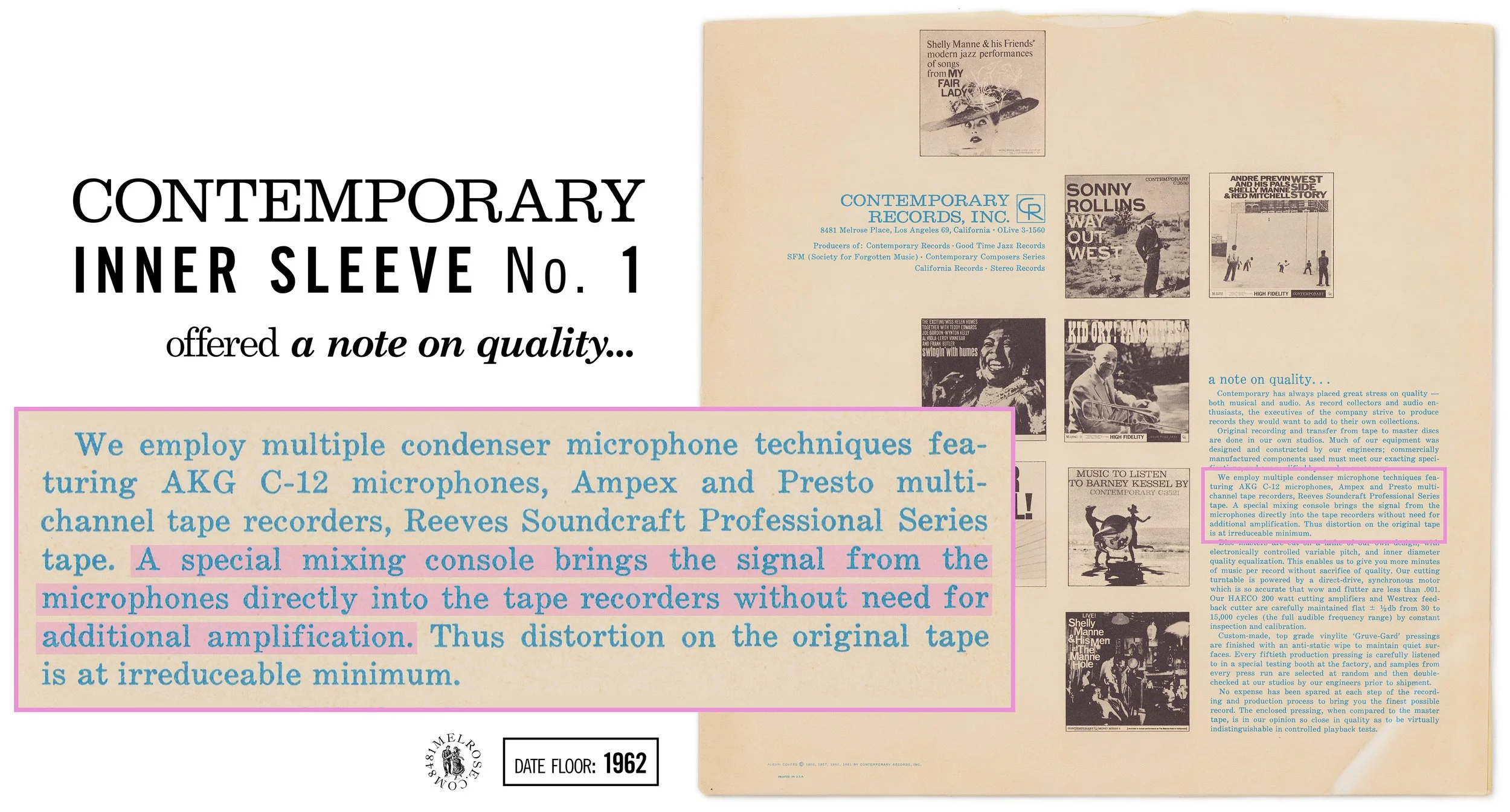

The series, which Ricker mastered alongside Bruce Leek, included three Contemporary titles: You Get More Bounce, At the Black Hawk Vol. 1, and Sounds Unheard Of! (We’ll talk more about Stan Ricker’s sonic approach to these titles in the Reverb chapter below.)

The AP Revival Series also included three Art Pepper LPs originally recorded for Galaxy in 1985: New York Album, So In Love, and The Intimate Art Pepper. The first two were first released back in the 80s, but AP scrapped their illustrated artwork and installed covers more akin to Art’s Contemporary portraiture. The third album (Intimate) was then formed from leftover tracks of the other two sessions, with an equally visaged cover.

John Koenig was heavily involved in reissuing these Galaxy titles, producing and remixing the sessions.

Fantasy 45 Series 45rpm Reissues

(2002-2006)

Stan Ricker’s time at AcousTech ended not long after the AP Revival Series, when another cutting engineer was hired: Kevin Gray.⁽¹⁰⁾ Gray put the lathe to work cutting stuff for all comers, but the AcousTech docket remained heavy with Kassem jazz jobs like the Thelonious Monk Tenor Sessions boxset.

Partnering with Gray on a chunk of cutting work in this era was his former MCA colleague Steve Hoffman— who was at the time shepherding Marshall Blonstein’s audiophile shingle DCC Compact Classics (and had worked at AcousTech with Ricker on some of those DCC cuts).

In the early 2000s, Chad Kassem took on the monumental task of reissuing 100 titles from the Fantasy jazz catalogs at 45rpm. Cut all-analog from the original master tapes by Gray & Hoffman, the Fantasy 45 series collected the hits: Miles on Prestige, Trane, most of Monk and Bill Evans’s Riverside work, Chet Baker, Guaraldi, even some blues. 100 titles left room for just about everything.

That included plenty of Contemporary; nine titles were selected and reissued at 45: Way Out West, Ben Webster at the Renaissance, The Poll Winners, You Get More Bounce, Jazz Giant, Sonny Rollins and the Contemporary Leaders, Art Pepper + Eleven, Smack Up, and Intensity. Noteworthy for the 45rpm format and the cutting team’s conscious decision to omit outboard reverb (an approach Hoffman has taken in several other CR reissues for CD and SACD), these releases provide a close all-analog look at the what the Contemporary tapes actually sound like.

The AP Contemporary Series

(2015… aborted)

In the mid-2010s, Chad finally got around to the idea John Koenig had seeded decades earlier: that Bernie Grundman was the man to cut Contemporary titles. He licensed from Fantasy — now Concord — 25 Contemporary titles with plans to cut new premium reissues and release them with style and faithfulness akin to the 33rpm Prestige titles he was releasing at the time.

Two titles were cut in the first 2015 sessions, Way Out West and Sounds Unheard Of! Michael Fremer uploaded a video of one of these sessions, showing Bernie, Chad, and John Koenig hanging around the studio and talking CR history.⁽¹¹⁾

Soon after that, Concord revoked the licenses and aborted the series. Kassem cited new management at Concord as the upsetting factor here,⁽¹²⁾ and the deeper reason is easily identified: Concord made plans to launch Craft Recordings and sought to bring all high-end reissue work in-house.

A handful of hopeful test pressings exist from the ill-fated series, for both titles.

For years it appeared it was a dead-end; after the pivot, Craft released a Way Out West “Deluxe” box set using digital sources, to Michael Fremer’s chagrin⁽¹²⁾ and the confusion of many.

The AP/Concord relationship had seemingly been severed, and — in the opinion of many an audio forum resident, myself included — Craft was not moving its jazz catalogs in a particularly exciting direction.

Concord / Craft Recordings

Then, a few things happened.

In 2019, Blue Note launched the Tone Poet Series, a program of high-end reissues cut all-analog from original tapes and pressed at RTI — essentially a mimic of Music Matters fronted by MM co-founder Joe Harley. To put it mildly, the series was an immediate success and served as the perfect model for other rightsholders to position reissues towards the audiophile market.

Soon after that came COVID. Remember it? The pandemic put gasoline on the vinyl resurgence and pushed pressing plants to capacity. Limited audiophile releases began selling out in hours.

It became apparent that there was more than enough money to go around, and that a single firm attempting to service a catalog with the reach of Concord’s was leaving a lot of that money on the table. Craft, it should be noted, had no personal foothold in the business of manufacturing and had to wait out plants like everyone else.

So in 2021, Concord/Craft re-partnered with Chad Kassem and his pressing plant Quality Record Pressings, to plan out a series of Contemporary reissues under the auspices of the label’s 70th anniversary. And, yes, they hired Bernie Grundman to cut them all-analog from the original two-track tapes.

Between 2022 and January 2025, nearly two dozen titles have since been released, with all of the Bernie masterings also available in digital formats. With Craft subsequently re-launching the Original Jazz Classics initiative as an all-analog premium series and Jazz Dispensary dropping all-analog outside stuff with some consistency (they reissued Blackstone Legacy in 2023), Contemporary’s recordings remain in play for numerous high-quality reissues moving into the future.

As a side note, what happened to those Bernie Grundman 2015 cuts?

Sounds Unheard Of was eventually re-licensed to AP and reissued in November 2024 using 2015 Bernie metal.

Way Out West, however, was re-cut by Bernie in 2022 and slotted into Craft’s all-analog Go West boxset in 2023. The same version was broken out for individual release (as part of the AS Series) in December 2024.

The 2015 cuts of Way Out West remain unreleased.

Reverb

Contemporary’s raw performance captures — their session tapes — were cut and assembled into master tapes with no copies or generations in between. So there was a burden on those session tapes to be as polished as they could be.

This put a lot of creative responsibility in the recording engineer’s hands; responsibility they had to wrangle on the fly without break or quarter. That was more than enough— so if anything could be left until later, it was prudent to do so. One specific creative choice Contemporary deferred until the mastering stage was reverb.

Reverb is when a sound wave bounces (reverberates) off a surface and arrives at the listener slightly later than the primary wave. Our ears use this to interpret space, so reverb in recorded music can exploit the listener’s instinct to create the illusion of space. Recordings often have natural reverb printed to the tape, but many recordings over the past 50 years were captured “dry” using sound booths or baffles, with artificial reverb added in mixing.

For jazz in the 1950s and 60s, those sound booths weren’t really a thing (?) but artificial reverb was common. Rudy Van Gelder applied various forms in his studios.⁽¹³⁾ Even recordings made in gigantic rooms like Columbia’s 30th St. church occasionally piped-in additional reverb on certain mic feeds.⁽¹⁴⁾

The illusion of space could then be tailored for specific emotional effect. Many felt — and still feel — that outboard reverb could make recordings softer, more pretty, more soulful. Lester Koenig was one of those folks. Artificial reverb became a fundamental step to make the Contemporary stockroom feel bigger and warmer.

The choice, then, was where exactly to apply it. Many labels applied reverb at the recording stage, which locked the mixer’s on-the-fly reverb moves in stone. A creative risk. Others recorded sessions dry before adding reverb to 2nd-gen “cutting masters,” which allowed more freedom but added tape noise and distortion. A sonic compromise.

Lester surely considered these drawbacks, and having his own lathe meant he could avoid them. He could defer reverb until the disk cutting stage itself, where it could be carefully perfected as he saw fit. Per John Koenig:

Our records from the '50s through the '70s were recorded dry. It was always intended that reverb would be added in mastering, and it was. (We had an EMT mono plate.) ⁽¹⁵⁾

The tool of choice was the EMT 140 reverb plate, introduced in 1957 by German firm Elektromesstecknik. Contemporary acquired one of the very first mono units, and despite EMT releasing a stereo model in 1961, Contemporary stuck with that mono plate for another two decades. That very plate now resides at Bernie Grundman Mastering in Hollywood.⁽⁸⁾

2016 look at Bernie Grundman Mastering's EMT plates. The left two are mono (one reportedly being the original Contemporary unit) and the right most is stereo. (Source: One of Fremer's potato videos⁽¹⁶⁾)

EMT 140 mono unit. Source: an original manual from 1958.

These were gigantic but smaller than the structural rooms used in years previous. Early attempts at moveable reverb units — such as a spring reverb used by Rudy Van Gelder in the mid-1950s⁽¹³⁾ — sounded woefully artificial against the EMT, which quickly became industry standard in studios worldwide.

The EMT design is conceptually beautiful and simple from afar. The incoming audio signal (ie. the dry music) vibrates a large metal plate, meanwhile a microphone on the other side picks up the reverberation of the plate and returns that echo to the studio. The length and “size” of the reverb can be controlled by physically dampening the plate, and additional adjustments could be made to the return signal when received back at the studio console.

Contemporary’s EMT was connected by send-and-return to the mastering console, so reverb was controlled alongside other mastering variables. Bernie Grundman has described Lester’s philosophy when applying reverb:

For most of the albums, he didn’t want to draw attention to the fact it was something artificial. He was just looking for some ambience, just to create a little bit of an environment… we’d raise the reverb until you’d start to notice it, and then we’d pull back. So it was affecting it, but you weren’t aware of it so much. That’s what he was trying to do, be subtle about it.⁽⁸⁾

Those instructions are obviously mega subjective and subject to taste, so reverb has varied a bit by era, engineer, and title. This is especially true after 1984, when Contemporary left Koenig control and the question of reverb fell to Fantasy’s engineers. The sonic handover proved memorably vexing for John Koenig, whose reverb and EQ recommendations were rebuffed by George Horn at Fantasy.⁽¹⁷⁾⁽¹⁸⁾

This is not to say that adding reverb is always the correct decision. Opinions vary. Some modern engineers (like Steve Hoffman⁽¹⁹⁾) think CR’s stuff sounds more natural without. Others have elected to apply reverb, with many such efforts have cranking far beyond the “subtle” effect Lester prescribed.

Which gets us to a key point: as mastering engineers are entrusted with dialing in (or eschewing) this highly variable aspect of the recording itself, their personal taste becomes a critical ingredient in the sound.

“Jazz Me Blues”

Here are three stereo digital flavors of track B1 off Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section. Keep in mind these are converted/squished files and each was a different source format, so this is hardly a true comparison of sound quality. Think about reverb here.

The Doug Sax (1992) and Bernie Grundman (2021) sound not so dissimilar (vis-a-vis reverb at least), but Steve Hoffman’s dry mastering (2016) provides context for how significant a difference this layer actually makes.

“Gone With the Wind”

3607 Intensity is a particularly romantic collection with significant reverb applied on its vintage Koenig-era cuts. The first clip below is from one of those, the LKS-248-D3 cut from the late 1960s:

Consider how 8481’s mono EMT smooths out Art’s tone and unifies the soundstage in the first clip. Similarly we can appreciate how the crisp authenticity of Hoffman’s presentation unveils the original performance while preserving its rhythmic coherence. There can be more than one right answer.

The second example is the 1997 DCC Compact Classics CD reissue — another Steve Hoffman counterpoint which presents the bare tapes dry:

“Complete”

Various iterations of You Get More Bounce with Curtis Counce! (aka Counceltation) expose both the positives and negatives of artificial reverb. Take the opening track “Complete,” first on the original stereo LKS 109 D1 cut, which was mastered in the early 1960s but unheard until 1972:

The most recent release of this title — the 2023 Acoustic Sounds Series cut by Bernie Grundman — returns reverb to the title, this time applied by BGM’s stereo EMT plate. Compared against the two earlier dry examples, the reverb is obvious— but in isolation it’s tasteful and restrained:

The Analogue Productions 45rpm reissue from 2003, cut by Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman at AcousTech with no reverb, echoes the flavor of the D2A cut and adds even more detail on top and bottom:

Consider the effect created specifically by the stereo EMT plate used for the 2023 cut in comparison to Contemporary’s mono plate used for the D1 cut 50 years earlier. Whereas reverb on 8481 Melrose cuts helped to unite the soundstage at a phantom center, the stereo plate creates two separate left and right spaces. Again, it’s not about right and wrong answers, but this is its own different flavor from everything above.

The next example is chronologically out of order but left for last as it needs the most discussion. It’s the 1996 Analogue Productions Revival Series reissue cut by Bruce Leek and Stan Ricker. And, well, it needs to be heard to be believed:

The next set of lacquers were cut in the early 1980s, after the shuttering of Contemporary’s studio at 8481 Melrose. LKS 109 D2A shows some serious evolution made in cutting tech and has seemingly no additional reverb applied:

This bonkers reverb appears to be courtesy of the Lexicon 300 “digital effects system” which featured analog in/out sandwiched around DSP-based digital reverb. Ricker once detailed his use of the Lexicon and John Koenig’s response to the sound of the Revival reissues (bolding mine):

That was my first experience with the Lexicon 300 as an echo machine...

I wanted two kinds of echo. It's just the way I conceived of it. Like these guys playing on a nice big stage in an empty concert hall. So, you have one set of acoustics which is the relatively rapid first reflection time, you see, of the stage environment, laterally and vertically. But then you have a longer time period of the reverb that you'd hear out in the hall. … So, there's two sets of echoes on this record because the machine was capable of generating two entirely different sets of echo time concepts. I didn't really know how it sounded until I played it back here on my system at home. I've got to say I was really impressed with it. Now, John Koenig … he thought there was too much echo … I told him, "I like doing reissues, and I think I do them well, but part of what reissues are all about is bringing out the best of yesterday's recordings with today's technology." And I didn't feel I could just turn my back on the possibilities that the new reverberation devices offer; just making it sound like a couple of echo plates or dry rooms didn’t cut it for me at all.

— Stan Ricker ⁽¹⁰⁾

Ricker’s viewpoint reflects a common dilemma: when mastering music decades post-recording, do you keep close to the producer’s original intent or filter the sound through the tastes of the present? The reverb on Bounce certainly feels far afield from anything released under the Koenigs.

Personally, I doubt that these Lexicon’d cuts were actually in step with the tastes of any present. This level of added reverb takes away from the uniqueness in the recording itself. It’s not supplementing the music; it’s overstepping it.

Still, it’s bold. It’s memorable. You can hardly fault Leek & Ricker taking a risk when so many engineers seem reticent to impose any point of view on a piece of music. Consumers seem perennially baffled that a mastering engineer might be more than a robot at the controls, and I salute this example as a fuck you to those people.

The engineer is one of the musicians. And they make creative decisions you might not love.

Tape EQ Curves

& Noise Reduction

Much has been made of Contemporary’s EQ idiosyncrasies, specifically what (if any) noise reduction EQ curves Roy DuNann and/or Howard Holzer built into their stereo tape decks. The supposed problem being that post-Koenig reissues have reportedly neglected to compensate for the original tape machine’s EQ tilt, resulting (reportedly) in harsh or overbright masterings.⁽¹⁷⁾

Details of this EQ are difficult to pin down, and multiple trustworthy sources’ recollections of the facts subtly conflict with one another. So we should accept that hard conclusions will be elusive.

First let’s establish some clarity vis-a-vis the recording process. Contemporary (from 1956 to at least 1961) ran an Ampex 351-2 stereo tape deck (later a Presto machine of unknown model) which was fed by a custom-built 8 to 10-input passive stereo mixer⁽²¹⁾.

One of the few public photos of Lester Koenig and Roy DuNann at 8481 show the tape deck and mixer in situ:

Lester had a small collection of Neumann and AKG mics with high enough output to be fed directly into the mixer sans the usual mic preamp stage in-between.⁽²¹⁾

The simplicity of that signal path was critical in achieving Contemporary’s unique, clean sound. Per John Koenig, “the direct line from the microphone to the Ampex machines was the best line.”⁽²²⁾ And Grundman: “Practically everything was coming straight from the microphones directly into the tape.”⁽²²⁾

So at the end of that recording chain came the tape machine and the tape stock piping through it. Contemporary used Ampex 111 and the similar Reeves Soundcraft “Blue Diamond” tape.

Recording to tape generally means applying some kind of noise reduction scheme to correct for the inherent weaknesses of analog media: high frequency noise and low frequency oversaturation. The former can obscure the recording itself while the latter makes it difficult to capture a full-bandwidth signal undistorted.

So, throughout the history of consumer media, EQ curves have been used to limit these effects.

when recording to tape, an EQ curve is applied to the incoming signal to turn down low frequencies and boost high frequencies by significant multipliers. This allows low frequencies to live on the tape without oversaturating it.

When playing back the tape, an inverse of the EQ recording curve is applied such that the signal is restored to the correct frequency balance… and in the process of pulling down the high frequencies, the tape hiss is reduced in equal measure.

The vinyl medium faces the same challenges and requires the same solution. The RIAA curve is applied to the signal when cutting the lacquer; an exact inverse curve is then applied by your phono preamp when playing the record.

RIAA is just a specific industry standard introduced in the early 1950s; additional standards include NAB and IEC. It’s not super important to get into their details or turnovers or shelfs or whatever, not that I could, but we need to understand that “correct” playback of a medium means applying the exact inverse of the curve used when creating it.

The two steps can be referred to as pre-emphasis (during recording/creation) and de-emphasis (during playback).

So why are we talking about this? It’s evident that there was at least some non-standard noise reduction schemes used in Contemporary’s recordings. Thomas Conrad’s 2002 Stereophile article “The Search For Roy DuNann” touched on it very briefly (bolding is mine in all the quotes below):

Another step that Roy took during mastering was to roll back the 6dB high-frequency wide-curve boost that he had tweaked into the Ampex during recording. Long before Dolby, Roy was figuring out his own methods for reducing tape hiss.⁽²³⁾

It’s unclear who provided Conrad the specific 6db number. Based on the others quoted in Conrad’s pages, perhaps DuNann himself, or John Koenig, or Bernie Grundman. John Koenig has spoken directly about this subject several times, often in reference to Fantasy Studios’ decision to ignore his instructions for Contemporary’s idiosyncratic noise reduction scheme(s):

Roy DuNann… devised an early noise reduction system that involved referencing the record electronics of the Ampex 350-2 tape machine so as to pre-emphasize the high end a couple of db and then compensate for that by referencing the machine on playback so as to bring the high end back down the same amount, thus bringing quite a bit of the tape hiss with it. I tried to explain this to the engineers at Fantasy when they took over the label, but they didn't want to hear it.

— John Koenig, 2011 ⁽¹⁷⁾

Bernie Grundman has echoed this:

[Contemporary] had their own form of noise reduction; Roy had a way of changing the EQ curve so that he recorded more top end on the tape machine, but not too much top end. Those recordings tended to be quiet, which was even more amazing.”

— Bernie Grundman, 2022 ⁽²²⁾

In an earlier conversation, BG conveyed some specifics:

A trick that Mr. Dunann would use when recording at Contemporary is as follows: he would be recording at 15 ips, however he would set the NAB curve on the tape machine to 7.5 ips. This way he would achieve a cleaner sound in the high end because the NAB curve for 7.5 ips is steeper at around 10k, and “you can get away with it with Jazz because there’s not that much information up there”

— Bernie Grundman, 2017 ⁽²⁴⁾

As we try to absorb that, see the Ampex amp front panel:

So I get there are two switchable EQ settings. However I’m not sure how the NAB thing could be accurate, because NAB curves for 15ips and 7.5ips are, as I understand it, identical.⁽²⁵⁾

More convincing to me is the suggestion that DuNann and Holzer simply designed custom curves by replacing resistors and capacitors with non-stock values, thus designing their own proprietary EQ curve(s). John Koenig’s statements seem to agree more closely with this idea:

A lot of the OJC recuts sounded terrible because up at Fantasy, they ignored the fact that we didn't recording use the RIAA curve, but rather, an ad-hoc noise reduction regime devised by Roy DuNann.

— John Koenig ⁽¹⁵⁾

What would creating an ad-hoc “noise reduction regime” look like? Well, here’s the Ampex amp schematic and the components one would need to change to alter the stock EQ curves:

Simple enough, in principle. There are separate circuits governing EQ on the recording side and playback side, which makes sense because they’d each be applying inverse curves. However, both recording and playback EQ are toggled high/low from a single switch.

I think this will be important because — stay with me — at least one source refutes the widespread application of non-standard EQ at 8481.

That source is engineer Steve Hoffman, who’s mastered dozens of Contemporary reissues on various formats. As host of the most popular online music forum, he’s had many opportunities to offer his take, and he claims the issue is fairly isolated:

I'm speaking of the myth that the treble was cranked up during the recordings so it could be lowered during cutting, thereby lowering tape hiss along with it. I've only found this treble lift on a few Contemporary Studio albums, like Pepper/Intensity, Previn/Bells Are Ringing, etc. It's just about +2 at 10k, that's all. Most of the Contemporary stuff I've worked on have no treble lift at all.

— August 24, 2022⁽²⁶⁾

… not all of the Contemporary/Good Time Jazz stuff was recorded in that style. Art Pepper/Intensity was, Art Pepper + 11 was NOT. So ya gotta be careful in mastering.

— April 9, 2024 ⁽²⁷⁾

Meanwhile, some of his statements on the subject make the issue sound a bit larger— or at least indeterminate in size:

Thinking about it, some Contemporary titles (like "Harold In The Land Of Jazz") engineered by Howard H. have a weird upper midrange boost that is really annoying. They have to be reduced starting around 6k or else the music sounds strident and harsh. Mostly 1957 stuff. After that whatever he was doing, he stopped..

February 13, 2022 ⁽²⁸⁾

He’s touching on something that’s become apparent to me after hearing enough CR records: that frequency balance put to tape clearly varied date-to-date. He’s also saying this was not by chance: the engineers often changed and modified and improved their processes, resulting in — seemingly — multiple approaches to pre-emphasizing the tape machine at recording.

So let’s think back to the Ampex front panel and internals. If there were multiple noise reduction curves used for different Contemporary recordings, the tape machine would probably have been tweaked only on the record side. Why? Because the playback side had to be capable of handling any set of tapes at any given point. This could be for simple playback, dubbing, or for transfer to the cutting amps for mastering.

Moreover, there are — apparently — tapes that follow pretty standard noise reduction such that no playback tweaking would be necessary.

So perhaps the low/high knob was used on the Ampex to set Contemporary-specific EQ (CR EQ) on one-setting and standard noise reduction EQ (standard EQ) on the other. Thus they could set it to CR EQ on recording but would switch it to standard EQ when playing back because different dates might have different EQ. Leaving playback at standard EQ would have allowed them to be flexible date-to-date and track-to-track to handle differences between recorded noise reduction curves.

So how were any high frequency boosts actually addressed on playback?

Supposedly the engineers made notes on the tape boxes. Hoffman has, again, spoken to this:

I follow the instructions written by Roy DuNann or Howard Holzer (or Les Koenig himself) on the tape boxes… If the signal was boosted 6 db in recording and reduced 6 db in cutting, I did the same thing.

— April 9, 2024 ⁽²⁷⁾

Here’s what one of those boxes looks like:

Unfortunately I don’t have more examples. I’m not a cutting engineer, but to me these notes look sloppy and imprecise, which makes it difficult to fault any engineer who discards them and opts for whatever they think sounds best.

Those who actually absorb these notes — if possible — seem likely to read them as suggested roll-offs intended for stereo’s nascent years rather than directives necessary for faithful transfer. Hoffman, for example, has sought to “improve on what [DuNann and Holzer] were doing in mastering” because “sometimes compromises had to be made in 1958 that we don't have to anymore in disk cutting.” ⁽²⁷⁾

He’s correct there. And I’d say it’s a good thing for engineers to have latitude to use their own ears.

On the flipside, this puts additional creative burden on the mastering process which, in the case of Contemporary, has created significant variance between versions of the same material. Some of that is intentional, but some of it could be caused by engineers lacking access to the recording notes, or those notes being too unclear to be trustworthy.

Which titles received a top end boost?

From the outside looking in, it’s impossible to know 100% which titles have their top end boosted beyond standard EQ and which don’t. I’m not going to try to dissect the multiple forms of CR noise reduction because I really have no line of sight on specific data.

But we can try to listen for it. Comparing early Contemporary masterings (cut at 8481 Melrose) to those cut in 1980-83 — after the closing of 8481 Melrose but before the sale to Fantasy — has been somewhat illuminating. The cutting facility is still unknown for this period, but these lacquers were plated by SLM and assigned SLM delta plating codes above 350ish (see Reading Runouts Pt. 2).

Having compared these against earlier cuts where possible, I’ve come to believe these early 80s lacquers are cut flat with whatever standard tape EQ applied (NAB probably) and no “creative” EQ beyond that. Which is strange, I guess, because John Koenig was still running the label at that point and specifically — after 1984 — expressed displeasure with Fantasy not de-emphasizing the tapes properly.⁽¹⁷⁾ So perhaps I’m full of shit here.

Anyway— most of these early 1980s cuts, especially those recorded after 1958, sound unbelievable, hot, and specifically solid state in a way totally dissimilar to the system at 8481 Melrose. Some of these cuts do however sound a touch unnatural on top and bright in a way their 8481 Melrose versions never did.

The vague time period for those wonky recordings, I’ve found, is 1957. Way Out West, Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section, You Get More Bounce. Then again, I heard a similar tilt on A World of Piano, recorded in 1960. So the data, unmeasurable to begin with, is still too messy to depend on. Realize, also, that these are super subtle sonic differences; many listeners might not notice or might even prefer the upwards tilt.

Perhaps as time goes on, access unfolds, and knowledge grows, we can uncover more detail about Contemporary’s tape EQ curves. Still, hard answers will likely remain elusive, so the standard maxim remains in effect: trust your own ears.

Sources

Boden, Larry. Basic Disc Mastering. 1978. 3rd ed., 2022.

Jazz Discography Project. “Contemporary Records Discography Project.” Jazz Discography Project, https://www.jazzdisco.org/contemporary-records/. Accessed 2020.

Kassem, Chad. “From Halfway House to Vinyl Powerhouse: The Full Interview with Chad Kassem.” PMA Magazine, interview by Gilles Laferrière, Apr. 2023, https://pmamagazine.org/from-halfway-house-to-vinyl-powerhouse-the-full-interview-with-chad-kassem/. Accessed 2024.

(1) “Fantasy Records.” The Saul Zaentz Company, https://www.zaentz.com/fantasy-records.html. Accessed 2024.

(2) Sutherland, Sam, and Peter Keepnews. “Blue Notes: ‘Contemporary Returns in “Classic” Style.’” Billboard, vol. 97, no. 6, Feb. 1985, p. 33. Google Books.

(3) Koenig, John. “Membership Spotlight: John Koenig.” Cello.org, 2004, https://www.cello.org/Newsletter/MemberSpot/koenig.htm. Accessed 2023.

(4) Sutherland, Sam, and Peter Keepnews. “Blue Notes: ‘Contemporary Finally Joins the Fantasy Family of Labels.’” Billboard, vol. 96, no. 43, Oct. 1984, p. 46. Google Books.

(5) “About Us - Horn Mastering.” Horn Mastering, 2021, https://hornmastering.com/. Accessed 2023.

(6) “Anne-Marie Suenram: Engineering Credits.” Suenram.productions, 2021, https://suenram.productions/resume.php#. Accessed 2024.

(7) Taylor, Joseph. “Vinyl from Kansas.” Soundstagehifi.com, 1 July 2014, https://www.soundstagehifi.com/index.php/feature-articles/on-music/737-vinyl-from-kansas. Accessed 2024.

(8) Acoustic Sounds. “Bernie Grundman and Chad Kassem Discuss the Upcoming Contemporary Series.” YouTube, 8 Apr. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a7tUfTL2U_Q. Accessed 2022.

(9) Koenig, John. Liner notes. Ben Webster at the Renaissance. Ben Webster. Analogue Productions, 1993. Vinyl.

(10) Ricker, Stan. “Stan Ricker: Live and Unplugged. True Confessions of a Musical & Mastering Maven.” Enjoy the Music.com, interview by Dave Glackin, 1998, https://www.enjoythemusic.com/magazine/rickerinterview/ricker12.htm. Accessed 2024.

(11) Analog Planet. “Bernie Grundman Mastering Prepares to Cut Contemporary Jazz Titles.” YouTube, 4 June 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cimwJwBKg4. Accessed 2019.

(12) Fremer, Michael. “Sonny Rollins ‘Way out West’ in Deluxe Box Set from Concord’s Craft Label.” Analog Planet, 27 Jan. 2018, https://www.analogplanet.com/content/sonny-rollins-way-out-west-deluxe-box-set-concords-craft-label. Accessed 17 Dec. 2024.

(13) Capeless, Richard. “Visions of a Larger Soundstage.” RVG Legacy, 2020, https://rvglegacy.org/visions-of-a-larger-soundstage/. Accessed 2022.

(14) “Frank Laico: Recording Engineer, Columbia 30th Street Studios.” LondonJazzCollector, 11 May 2019, https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/2019/05/11/frank-laico-recording-engineer-columbia-30th-street-studios/. Accessed 2025.

(15) Astor, Myles B. Comment on “Rudy Van Gelder versus Roy DuNann.” Audionirvana, 2 Mar. 2020, https://www.audionirvana.org/forum/music/audiophile-issues-reissues/132338-rudy-van-gelder-versus-roy-dunann#post132399. [Note by John Koenig]

(16) Analog Planet, and Michael Fremer. “More from Bernie Grundman Mastering.” YouTube, 9 Feb. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c5MsUZo-ZCY. Accessed 2022.

(17) Bruil, Rudolf A. “History of Contemporary Records.” Sound Fountain, 2010, http://www.soundfountain.com/contemporary/contemporary.html. Accessed 2019.

(18) “‘Pressed for All Time,’ Vol. 9 — John Koenig, Sonny Rollins, and William Claxton Talk about Rollins’ 1957 Album Way out West.” Jerry Jazz Musician, Aug. 2016, https://www.jerryjazzmusician.com/pressed-for-all-time-vol-9-john-koenig-sonny-rollins-and-william-claxton-talk-about-rollins-1957-album-way-out-west/. Accessed 2023. (Excerpt from book “Pressed For All Time” by Jarrett, Michael.)

(19) Hoffman, Steve. Comment on “Contemporary Records 70th Anniversary Reissue Series.” Steve Hoffman Music Forums, 12 Mar. 2024, https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/contemporary-records-70th-anniversary-reissue-series.1093420/page-127#post-34075325

(21) Acoustic Sounds. “An Interview with John Koenig, Former President of Contemporary Records.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 22 Apr. 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAsuVLN_lyo. Accessed 2022.

(22) Amorosi, A. D. “The Sound of Contemporary Records.” JazzTimes, 8 Apr. 2022, https://jazztimes.com/features/profiles/the-sound-of-contemporary-records/. Accessed 12 Nov. 2024.

(23) Conrad, Thomas. “The Search for Roy DuNann.” Stereophile.com, Apr. 2002, https://www.stereophile.com/interviews/402roy/index.html. Accessed 2020.

(24) Astor, Myles B. Comment on “Rudy Van Gelder versus Roy DuNann.” Audionirvana, 2 Mar. 2020, https://www.audionirvana.org/forum/music/audiophile-issues-reissues/132338-rudy-van-gelder-versus-roy-dunann#post132400. [Bernie Grundman interview by Tommaso Gambini, 7 Jul. 2017.]

(25) Elliott, Rod. “Hi-Fi Tape Preamp (NAB/ IEC Equalisation).” Elliott Sound Products, 2023, https://sound-au.com/project247.htm. Accessed 2025.

(26) Hoffman, Steve. Comment on “Contemporary Records 70th Anniversary Reissue Series.” Steve Hoffman Music Forums, 24 Aug. 2022, https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/contemporary-records-70th-anniversary-reissue-series.1093420/page-75#post-30279352

(27) Hoffman, Steve. Comment on “Howard Rumsey Lighthouse All-Stars "Music For Lighthouse Keeping" Roy DuNann, original vinyl amazing.” Steve Hoffman Music Forums, 9 Apr. 2024, https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/howard-rumsey-lighthouse-all-stars-music-for-lighthouse-keeping-roy-dunann-original-vinyl-amazing.1199294/page-2#post-34251862

(28) Hoffman, Steve. Comment on “Contemporary Records jazz titles recorded by Roy DuNann: remastering techniques and challenges.” Steve Hoffman Music Forums, 13 Feb. 2022, https://forums.stevehoffman.tv/threads/contemporary-records-jazz-titles-recorded-by-roy-dunann-remastering-techniques-and-challenges.1132913/#post-28918365