Guiding Philosophies

Vinyl isn’t easy, but perhaps that’s part of the appeal. The act of putting physical effort into music playback places more emotional investment in the act of listening… or so us vinyl freaks would have you believe.

We’d also have you believe that vinyl is satisfying. Forget the pops and ticks and crackle — or at least accept them — and you open yourself to a totally different camaraderie with music. It’s heavy, it takes up space and you can see it from afar. It’s exciting to see it spinning. It’s enlivening to surf through a store and acquire something you can use and play repeatedly into the future. It’s warming to share the love of it with others. Or so we say.

This conveniently ignores the numerous downsides inherent to the format and the gaping pitfalls it can open up in a lifestyle. Gathering obsessive bits of pressing arcana begins to numb your once-happy love of listening to music until trudging through store bins becomes the intellectual pursuit of the very best versions, bloodless, exhausting, the end result only discontentment with the records you already have.

This is only half the pain, of course. The other half finds you, night after night, wrestling the complex physics of a tonearm and the tiny electrical nuances of a phonostage while a voice whispers in your ear: you haven’t spent enough to get good sound. Suddenly it's 4am and you have to be at work in four hours but you're buzzing and waist deep in the detritus of your own confusion. Forum post after forum post, you scour the web looking for equipment upgrades, truffling the ground for new places to sink the money you may or may not have.

You're a junkie. You don't enjoy this anymore but you can't stop. You’ll endure anything in the hopes of finding the fun again. And, like acid, this addiction erodes your ability to think and leaves you wandering aimlessly for answers.

The brain wants simple answers

and like water pushed through a puck of espresso, it seeks the path of least resistance. The more impassible the problem, the more furiously we seek a channel.

Vinyl is like that. Any question has a hundred answers. Pressings and reissues and master tapes are vague argot made muddier by conflicting bullshit found everywhere, and the variables of playback are minuscule, endless, and frustrating. We struggle to accept complexity. We have to tame it. Neuter it.

So the vinyl listener can fall easily into honey traps promising simplicity. One of these — a security blanket common among jazzheads in particular — is the generalization that “original pressings are the best.” This is not always wrong, but always wrongheaded: a wild oversimplification of physical and technological realities such that it calls into question the claimant's authority to be spouting an opinion at all.

For many labels, "original pressings" — or perhaps more intelligently specified if still problematic, original mastering — point to a creative connection with the artists and original producer. I want the sound the artists intended, you say. On some level, I get that. There are plenty of cases where this simplemindedness might serve you well.

But you need to be smarter when it comes to Contemporary.

Contemporary is a unicorn.

A few things set it apart: from 1958 to 1980, they cut their lacquers (ie. mastered their LPs) in-house. And unlike Blue Note or Prestige or other coveted indie jazz labels, Contemporary remained independent through multiple generations, such that the original artistic intent was the reference point for reissue after reissue and round after round of lacquer cuts. For most of Contemporary’s run, the original producer oversaw vinyl releases in every aspect. After his death, his son took the torch, cutting lacquers himself by referencing past mastering notes and supplementing them further. Contemporary was a unique house, and its vinyl history is worth exploring and honoring in total.

So this is not a how-to guide for identifying first pressings.

Well it's not JUST a how-to guide for identifying first pressings. It's a devotedly accurate, title-by-title guide to identifying any US pressing up to 1984, with equal weight given to them all. Hand in hand with that:

A central goal of this site

is to challenge the idea that any conversation about vintage records, jazz in particular, need be centered around money and sales and value and rarity. In the present day, when used vinyl is ascending rapidly in price no matter the provenance, Contemporary Records is, to my mind, an honest reprieve. Contemporary’s best stuff has slipped through money-drunk collectors' couch cushions and trickled down to where actual listeners live.

This site is for those listeners. But it's also a place for anybody who chooses information, accuracy, honest deduction, and transparency over vague assumptions and myth. Sources will be cited, actual research shared, data analyzed in depth. It's been said that the history of Contemporary Records is opaque and undocumented. Let’s fix that.

In that effort, I want to share a space where finding music on vinyl is a journey of discovery and reward rather than frustration, jealousy, and debt. I hope that traveling down the Contemporary rabbit hole and paging through this site can be like living inside that first moment of elation when you find something cool in the bins, this time with the feedback of knowing here are the reasons why it’s special.

At the end of the day, I hope to honor the artists, producers, engineers, and others who’ve played a part in the Contemporary story, at 8481 Melrose Place and beyond.

Methods & Best Practices

The following is very theoretical and perhaps unreadable. Sorry in advance. I expect very, very few people to get through this page. But here’s a bunch of thoughts for how I’m trying to approach the research for this site.

Title by title by title.

Contemporary changed fluidly from 1955 to 1984, so — like tree rings hold clues of an historical climate, each era’s new titles expose the label’s approach in their time. The frameworks, design schemes, and partnerships revealed can in turn be used for bucketing reissues into specific timeframes, as most of the work here is in dating reissues of earlier titles (eg. a 1981 reissue of a 1960 title).

But it’s not that simple. New titles can be used to bucket reissues in time, but this will pretty often steer us wrong. To get to the truth takes concentrated title-by-title attention and a serious collection of evidence. Generalizations aren’t going to help us much.

Identifiers

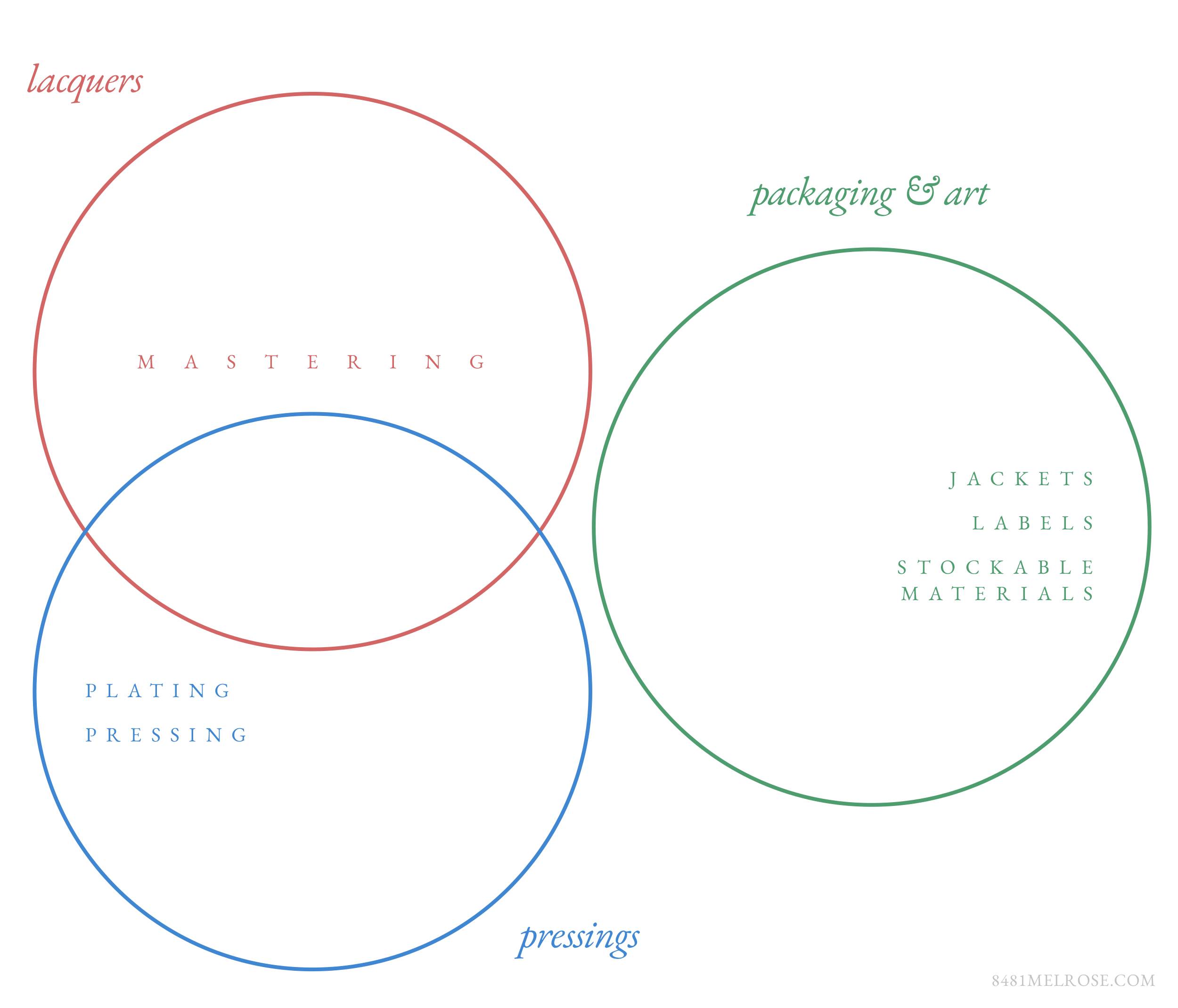

Changes in Contemporary’s end product (vinyl releases) were iterative. Which is to say that one variable changed at a time; each variable could change independently while other variables kept continuity back to the previous “release.” For example, jacket design might change with no impact whatsoever to the pressing inside, or pressing would move to a new plant but retain the same metalwork (ie. runouts) and packaging (ie. jacket) as before. Or any combination or mix of these or more finely defined variables. These variables, by the way, we’ll call identifiers.

Deliveries

In modern times we’ve become used to the vinyl reissue, a definitive checkpoint which — out of nowhere — brings an old title to market. When we look back at vinyl’s heyday, it’s easy to expect this same kind of clarity but it doesn’t really apply. If a title was released in 1960, it might have stayed in continuous print for the next twenty years while various pieces of the release (jacket, lacquers, labels) changed with time. Despite changes to those identifiers, at no point in that span could you call the release a reissue. There might be replacement lacquers cut, replacement jackets made, replacement labels printed. That was simply the normal way of things.

Thus the reality behind vinyl “originals” and later pressings was rather liquid and not like the “checkpoint” nature we know today. But the goal here is to frame the old school by using the new and apply checkpoint structure to liquid history so you in the year 2024 can have more concrete “versions” to point to.

So it helps to be specific about those “versions.” Pressing doesn’t make any sense for this, as it refers to several other things and is already confusing. So, to encompass the jacket and record, sealed and delivered to market, I’m going to call each “version” a delivery. Each delivery is unique in its identifiers; as soon as one identifier changes it becomes a new delivery.

Data considerations

How do we trace all deliveries of a title? We need a large sample size of LPs. The first hurdle, then, is data collection: we need to amass enough data points (records) to catalog as many variations of a title as possible. This takes a long time.

Criticially, the data needs to be clean, properly documented, and verifiable with images and detail. Which, again, takes a long time. This site has been two years in the works prior to launch because the data is scattered around the world and, once collected, requires a f***ton of time to process.

Fortunately, though, Data collects exponentially: five variations of one title are not just title-specific data; they are potential data for other titles when copies of those other titles are physically beyond reach. Fine granularity is not always easy to deduce in an extremely limited dataset such as vinyl I can afford to buy + online sale listings with good enough pictures so I sometimes have to extrapolate based on what I can get access to. (are you confused yet??)

So gaps are inevitable. Anywhere multiple identifiers change at the same time, there could be a gap where we’re missing a delivery. Or not— multiple identifiers simply could have actually changed together, eg. the labels and jackets both needed reprinting at the same time and simultaneously took on new designs. We don’t know what we don’t know. We have to run with the data we have at present and still be open to more.

Stockables

If we can clear data hurdles and sequence enough specifics, we also have to consider the minor but occasionally discombobulating phenomenon of stockable and leftover materials. A record label like Contemporary wanted continuity of materials on hand to keep production downtime at a minimum. Parts like jackets and labels could be stored for years until needed… and so they often were. So long out-of-date addresses or design schemes could suddenly appear in a new period with little connection to the label’s current at the time.

Another limitation: we can’t always assume that every identifier changed cleanly, ie. that one iteraton ended when another replaced it. We don’t really have data to establish that level of confidence. Sometimes, for example, multiple label colors were used interchangeably through a period of time. We have to account for this kind of comingling which can blur the divisions between deliveries.

Elective vs. non-elective identifiers

Identifiers can be divided into two categories: elective (those subject to the label’s creative choices) and non-elective (determined by a contractor’s best practices) categories.

I think these are fairly self-explanatory, at least superficially. Mistake is often made to consider every variable in a record package as non-elective because it makes it much easier to place deliveries in certain time frames.

As an example… the Stereo Records sublabel and design scheme was only active for new titles between 1958 and 1959, after which new stereo titles were released under the main Contemporary label instead. Many Stereo Records titles were then reissued on the Contemporary label with new packaging and label design closely matching that given to new titles in 1959-1961. So, many people would happily place the first Contemporary reissue of a Stereo Records title in 1959 because that’s when the Stereo Records label ended.

The mistake they’re making is that to assume that the sublabel name and design schemes were non-elective, and that — because the sublabel was retired — all subsequent versions of the title would by definition have to be on the CR brand. As if the label had no choice but to leave the Stereo Records brand in the past when, in fact, several titles continued to use Stereo Records branding well into the 1960s and some made it to the 1970s. We know this because of actual elective identifiers (pressing rings, jacket blank construction style, runout plating styles) that have a much stronger relationship with time.

ELECTIVE:

Jacket Design

Jacket print construction (front- or rear-wrap, etc)

Label color & design

Postal code (kind of)

Inners & extras

NON-ELECTIVE:

Pressing ring

Tip-on jacket blank construction (Gakubushi)

Plating marks, stamps, stamp styles, codes

Lead-out style (eccentric/concentric)

Lead-out LPI (I guess)

All the above said, elective vs. non-elective leaves a lot of gray areas. But this is a theoretical kind of conversation we don’t want to get stuck in for too long; the main point of this division is that we need to understand how powerful an identifier is insofar as it’s ability to place an LP delivery in time. Every identifier carries some timing nuance that we need to be aware of, but non-elective identifiers are, on the whole, far more powerful timing indicators than elective.

Date Floors & Date Ceilings

Let’s try to reframe all the above, using date floors and date ceilings. Every identifier has a date floor. Meaning there is a certain year before which that specific identifier could not have appeared. For example… the Contemporary “block banner” jacket with STEREO or HIGH FIDELITY branding (I’ll call this “1st Banner”) was designed in 1959. No such jackets appeared before May 1959…. making it the date floor.

That 1st gen banner design was used on new titles until about 1962 but reissues of several titles continued to use this 1st gen banner design for more than a decade. Some 1980s reissues use the banner design. What this means — beyond the fact that everything is title-specific — is there is no definable date ceiling for the 1st gen banner design scheme. That’s because it relies on a stockable material: design assets.

As you may then gather, most production identifiers will NOT have a date ceiling. This is because almost all of them involve stockable materials, such as jackets, labels, runouts (metal parts), design schemes, print assets, and inner sleeves.

Non-elective identifiers will generally have some kind of ceiling but it might not be for the final delivery. For example, lead-out LPI and plating stamp styles carry specific ceilings, but only for the time of lacquer cutting. Because the metal parts generated from that lacquer are stockable and usable over time, lacquer indicators don’t provide a ceiling for the actual LP pressed from them. Similarly, consider the non-elective Gakubushi jacket construction; finding this on a jacket puts a hard ceiling on when a jacket was assembled but, because a jacket can sit in a box for years waiting on a record, it provides no ceiling for the LP delivery it contains.

The ONLY production variables which will reliably be bound by a hard date ceiling are those locked in at the time of pressing. Variables like pressing rings or vinyl formulation (the latter of which won’t generally figure into our calculus). Pressing is not a physical material— it’s a service. A service is not stockable.

In Practice.

Let’s look at Way Out West in stereo.

Its first stereo release came in late 1958, under the brief-lived Koenig sublabel Stereo Records. Eventually this stereo title would be phased into the actual Contemporary label, but it first remained in print on Stereo Records for several years. Consider all the identifiers we see on the original release, below:

Any identifier — be it part of jacket design, jacket construction, runouts, labels, etc — could prove important in distinguishing this delivery from others. In this case, jacket construction is the critical identifier because, for this title, it is the the first identifier that changed. At some point, there arrived a largely identical delivery — same labels, same runouts, same jacket design — with a non-Gakubushi jacket.

That identifier alone carries a 1960 date floor. So the second delivery of the title also has a 1960 date floor, and we can start to put a ceiling on the 1958 first delivery. Not a hard ceiling, mind you; jackets are stockable, so the Gakubushi jackets could have hung around past 1960.

Basically you keep doing this, over and over. Finding the first variable(s) that changed, and iterating with as fine a granularity as evidence allows. We start to iterate identifier by identifier, like below:

We build a sequence of deliveries for a title, then use date floors, ceilings, and some logical reasoning to deduce when those deliveries were current.

You’ll notice these deliveries are chunked into broad, unsatisfying windows of time. Believe me, I’d love to get more specific. I strive to pin hard dates and years on deliveries but the data isn’t that clean. Remember we’re applying modern checkpoint structure onto a very checkpoint-less spectrum of time. We have to stay accurate to the data and not go more precise than it allows.