CONTEMPORARY RECORDS

label color & design

Label design and label color were two independent variables which, on occasion, will provide some valuable data for identifying Contemporary Records deliveries. Re: label color, the company swapped dominant paper stocks multiple times throughout the period 1955 to 1984, creating some murky borders in time by which we can (sort of, sometimes) bucket reissues.

Label design, meanwhile, was — because of the printing methods Contemporary employed — a wholly elective identifier which usually means nothing when flipping through versions of a single title. It’s a lovely study for those who find vintage designwork innately fascinating, but it won’t help much in identifying originals or pinpointing reissues in time. Still, some tourists to the subject of Contemporary seem to assume label design matters… and I feel the need to dissect why they’re wrong. For as long as that takes. So let’s hit design first.

After this tiny disclaimer… all labels have been scanned (rather than photographed) to maintain color and size consistency. The downside is this creates slightly darker images which struggle to recreate metallic tones and any kind of gloss. Some of this I can correct in post, but where surface finish is important, I’ve added in photographs which better capture reflectivity an an angle. And on other pages (Pressing History, for example), all label pictures have been photographed, which takes a lot longer but preserves more true-to-life brightness, texture, and depth.

Label design

You may be familiar with companies like Blue Note, Prestige, Riverside, Atlantic, etc. where the components printed or not printed on a center label (addresses, legalese, INC., etc) figure heavily into dating when a pressing was actually made. Contemporary doesn’t really fall in that pattern, partly because of the printing methods they used.

Let’s consider two very general methods for printing labels: 1-step and 2-step printing. 2-step was super common in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, and 80s when the vinyl output was voluminous and tech was a certain old way, but Contemporary (under Koenig ownership) didn’t use it through any of these periods. They always used 1-step.

The difference is what it sounds like: 2-step printing used two rounds of printing to complete the paper label. First was a “pre-printing” step where general label info and non-title-specific stuff was applied, thus creating a general company “blank” that could be used for any title. There was then, at some point, a second print run to actually imprint the title and track info. 1-step printing collapsed those steps into one, so the entire label was inked in one go.

The critical thing vis-a-vis our research is this: 1-step printing meant that reprinted labels (for reissue pressing runs) would probably not get updated in any way to adopt later-period company design. Which is to say: a reissue of a Contemporary title often featured the exact same label design as the original, even if done a decade or more forward in time. (Crucially, most of Contemporary’s center labels did not feature the company address, so Postal Code or address changes that might figure into Jacket Design would never make it to labels anyway.)

the Blue Note 2-step

Before we look at Contemporary’s design, let’s see how most companies handled their labels. Consider collector darling Blue Note, which left behind a well-known sequence of iterative label designs which — in part because of 2-step printing — changed pretty directly with time.

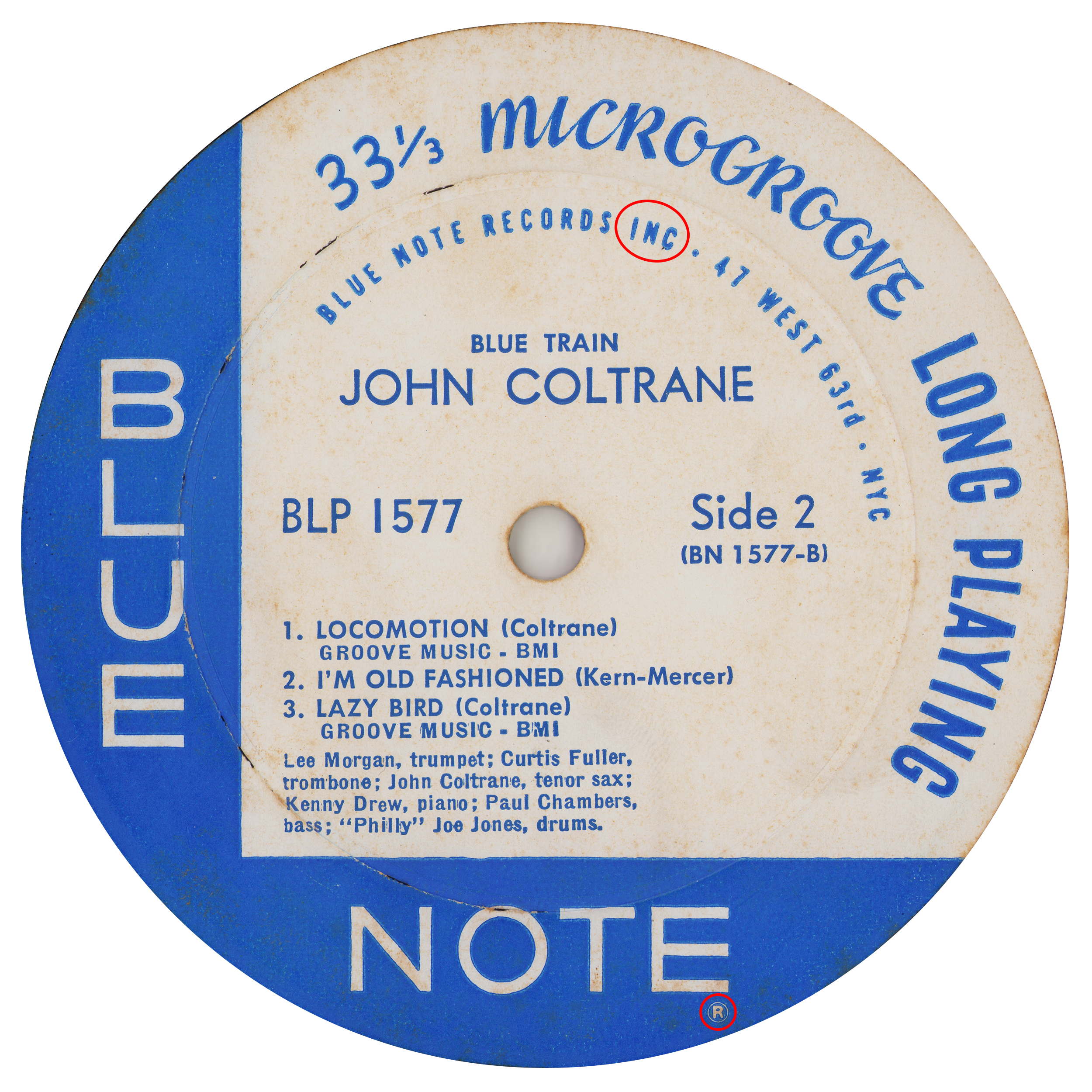

In the example below, you can see a circa-1959 pressing of John Coltrane’s Blue Train with the new incorporation marks (Inc. and R) not seen on earlier-issue 1957 labels.

Step 1 (1957)

Step 2

Pressed label (1957)

Step 1 (1959)

Step 2

Pressed label (1959)

The outer blue branding/addresswork, Inc. and R included, was pre-printed before the inner title info, which left to chance some subtle differences in ink color between the two steps.

Think about the logistics of 2-step printing. Blue Note would, in theory, order a giant stack of pre-printed labels without any title info on them then apportion from that stack a given amount to run for each title. When the entire stack of pre-printed labels was apportioned and used up, they’d order in a new stack… by which point in time, company circumstances might have changed to require new elements or changes in the pre-printed design.

Okay, but this all feels a bit complicated and unnecessary, right? Us digital dwellers need to think a little deeper about the actual analog techniques used to create these designs in order to understand why this actually made sense.

linecasting & variability

You ever wonder why popular titles from the 1960s and 70s could sport several different label variations and have them all be indistinguishably “original?” Those are just larger-scale effects of what we see with Blue Note.

At its heart is this: title and track information was delivered to printers as just that — information — rather than pre-stylized graphics. The printers then had the task of creating metal text slugs using their own linecasting machines and assembling a text layout by hand. Meaning that multiple printers working in parallel might create different spreads with different typefaces while the underlying pre-printed blank would remain the same. (What is linecasting, you ask? This YouTube video offers a better overview than I could.)

This starts to uncover the cost and efficiency benefits which drove use of the 2-step process. Company graphics involved ornate and complex graphics, so rather than repeating the setup/mould cost for these on every title (twice), a company could create one mould for the main graphics, run off an order of labels at scale, then do routine linecasting orders to complete the individual side information. This was faster and maybe cheaper than other alternatives.

This made label design under a 2-step process a partially non-elective question tied to the actual typefaces available on the printer’s linecasting machines. So the actual typefaces could become a powerful indicator of time if a new printer used a different brand of machines (Linotype, Intertype, or other) than previous ones. As a good example (yes, it’s Blue Note again), London Jazz Collector has dissected in depth the typeface variations on Blue Note labels after 1966.

This reliance on printers also made for quiet variations in spacing and layout. Assuming the text stack was not “bounced down” or copied to a reusable stencil/flong/mould (I really don’t have the vocab for this), layout depended on press workers setting “furniture” in a frame. Even with Blue Train, where the title information looks identical between 1957 and 1959 labels, we can see small variations in spacing between the different blocks of information.

Contemporary precision

Contemporary’s process left no typesetting or layout work to the final printers. Instead, the center label’s design was assembled as a complete unit (possibly using linecasting machines to generate the inner text slugs), then copied to some sort of final mould which could be used to print labels at scale.

unprinted stock

finished paper label

pressed label

The outer Contemporary branding was actually recreated on each and every label mould. How do we know this? For one, the spacing between the center elements and the outer ring was extremely even and identical across printings of a title. Contemporary utilized the entire center, positioning title info just millimeters from the outer ring without fear of elements colliding.

For another, color was always consistent across the entire print.

Elements of design

So these complete designs were created for every LP side. Others might have been considered this an expensive and inefficient faff, but Contemporary’s labels were more elegate, intricate, and beautiful for the choice.

Title, artist, and track information could be stylized and spaced however desired, and — the proof is in the pudding — Contemporary labels became a formal celebration of classic serif typography.

new titles, 1959-63

Contemporary started adding the CR logo to new titles in 1959. It was not a graphic constant like Blue Note’s Inc. and R, though; the CR could live in any one of three placements depending what space was available to it.

logo introduced 1959

logo inside the O

could also be here

or here

new titles, 1963+

The CR logo stopped appearing on new titles in 1963 (the first in sequence to not have it was 3611 The Great Jazz Piano). At the same time, titling was emboldened and STEREO denotation swapped sides with the Side indicator.

new titles

1970s & early 80s

As Contemporary entered a new decade, stylized title fonts began to trickle down from jackets to labels. John Koenig’s 14000 series carried this into the 1980s, still the core label design of the 3500 series remained in view, nearly thirty years on.

Reissue Label Design & Timing

Contemporary’s finalized label moulds could be stored and used in perpetuity with any hired printer. Assuming that any alteration would have required making a whole new mould, it’s unsurprising that Contemporary rarely revised its label designs. And, as a result, label design doesn’t speak to timing in any consistent way.

Consider again the CR logo which graced new title labels from mid-1959 to 1963. If all you know is 2-step printing using pre-printed company blanks, you might think the CR logo was automatically added to reprints of old titles’ labels.

Not so! Question the research of any source saying otherwise. Contemporary’s labels were complete finished designs, so many many titles released prior to1959 persisted through the decades without any addition of this logo.

One of them was C3523 Everybody Likes Hampton Hawes, which retained its original label design without change from 1956 to 1984, despite the title undergoing a wacky blue jacket overhaul in the early 1980s.

Catalog number/sublabel changes

Label design really only changed in events dramatic or unusual. They were also rarely revised alone; they were usually redundant to obvious movements happening beyond the labels. For example, the catalog number changes made to mono and stereo versions of My Fair Lady in 1959.

Catalog number/sublabel changes like this could barely be considered “label design” changes, though. These were obvious revisions affecting the whole delivery, notably apparent in dramatic rearrangements of jacket design.

Original Mono 1956

Mono M3527 1959

Original Stereo 1958

Stereo S7527 1959

Subtle changes

Other label revisions, like those involving song copyrights, could be sneaky and easy to miss. For example, the copyright language was quietly removed from S7562 Looking Ahead! labels in the 1970s. When this redesign was taking place, Contemporary took the opportunity to also refine box sizing around the STEREO marking. Still the design stayed predominantly intact and nothing new was flown in.

Wakefield codes (1981)

When Contemporary moved pressing to Wakefield Manufacturing in 1981 (see Pressing History), the plant’s own 5-digit tracking code was added to some labels. This was either discontinued or just a fluke, as it only impacted like four reissues all released in late 1981 at the very beginning of the Wakefield relationship.

The only instance where it matters much in identifying the pressing is the one pictured below, S7539 Counceltation. Keep in mind the pressing rings also changed, so looking for this code is not going to be important.

C3505 tape numbers

C3505 Hampton Hawes Trio shows a rare isolated case of a label design change happening independent of packaging.

In the 1970s, the title’s tape numbers were corrected to give side 1 the lower value (LKL 12-29) and side 2 the higher (LKL 12-30). It’s possible the album was originally intended with the opposite side order but was flipped following the test press stage, leaving the tape numbers in their original sequence. I don’t know exactly, but it wasn’t until 1975 or so, a few lacquer generations deep, that they were finally reversed to normal.

This triggered a tweak to label design. A very, very tiny tweak.

1950s-60s RCA Deep Groove

Early 70s RCA 26mm ring

1975-81 CBS-SM 69mm ring

1981-84 Wakefield

We could keep going on like this. The 1967 publishing credit on later reissues of Something Else. The disappearing stereo boxes on the late 70s copies of Something Else and Contemporary Leaders. The eventual font change on Smack Up.

Do you see what’s happening? These are a bunch of situational changes happening in relative isolation from one another, not some pattern wherein label design was revised across all titles at X point in time.

We don’t need to do this. Contemporary’s label design will not be helpful for identifying deliveries in any general sense. Where changes occurred, they remain title-specific questions, not Contemporary-wide ones.

Contemporary vs. Fantasy label design

After the Fantasy acquisition in late 1984, the outer “Contemporary Records” ring was preserved. But everything else was changed to Fantasy’s standard style which used rather lifeless linecasting or whatever for title information.

Koenig design (1950s-1984)

Fantasy design (1984-2020s)

I can appreciate Fantasy’s solid stewardship of their many jazz catalogs, but their woeful approach to labels deserves more ridicule. I don’t know if these workaday layouts represent an actual taste decision or they just tossed information to the printers to be assembled as rapidly as possible. Whatever the reason, their labels look like shit.

they went from this

to this. awful

Label color

is, on its face, totally irrelevant to sound or vinyl quality. Right? It’s just a circle of paper pressed into the plastic.

Yes, but label color often speaks to the timing of a specific pressing. This was especially important in the context of RCA Hollywood, which worked with Contemporary from 1955 to 1973 and put out some super scratchy stuff around 1968-71. In many cases, label color will be critical in separating that period’s sour output from the far-superior vinyl surfaces of earlier pressing runs.

In studying Contemporary’s later yellow label years (70s & 80s), color becomes a far less critical worry. Meanwhile the company hopped through a handful of pressing plants which each used unique pressing dies (unique in the context of Contemporary at least) which left plainly identifiable pressing rings in the finished disc. As discussed at Pressing History, those rings are a far more powerful identifier of time than the paper labels.

Label color is best discussed in more granular detail era by era, so let’s move into a timeline structure.

• 1953 •

In April 1953, Les Koenig stepped in to repress and distribute Sunday Jazz a la Lighthouse, a 12-inch LP recorded two months prior by Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars. Its first pressing had been a private canary-yellow run on the fledgling Lighthouse Records. For this wider second go, Koenig kept the label color, pausing only to give his Contemporary Records unit a presented by credit.

Concurrently he dropped Contemporary’s first two classical LPs, C2001 and C2002, on dark green labels with olive-gold text.

C301 Second pressing, Contemporary's first entry into jazz.

C2001 The first Contemporary classical title.

• 1953 to 1955 •

As Contemporary became a jazz-first label, it co-opted the Lighthouse yellow as its own primary color. Several 78rpm singles and 10-inch LPs would be pressed with yellow over the next two years.

C2515 10" LP, 1954

C2518 10" LP, 1955

• 1955 to 1959 •

When it came time to enter the 12-inch LP market with the C3500 series, Contemporary stuck to yellow.

• Popular Series, 1956 •

Contemporary launched the “Popular” 5000 series in 1956, and with it inaugurated the new black label with gold text:

C5001 Dig Mel Henke

C5002 Claire Austin Sings

C5003 Now Spin This!

Stereo Records

• 1958 to 1959 •

With a stereo market beginning to emerge, Les Koenig launched Stereo Records, a dedicated sublabel to catch stereo variants from all his brands. Stereo Records label design closely followed Contemporary’s design and co-opted the gold-on-black scheme of the Popular series, which had been dormant since ‘56. Unlike Contemporary’s labels, though, the Stereo Records name left a gap in the bottom center of the outer ring, where the label address and stereo 45-45 warning neatly found a place.

Stereo Records persisted for nearly a year and released thirty titles on black-and-gold. Despite its retirement in Spring 1959, several of these titles continued to be pressed on black Stereo Records labels for many years to come.

Contemporary Stereo & Mono

• 1959 to 1966 •

1959 marked a significant shift, as Contemporary chose to release all new titles going forward simultaneously in mono and stereo. The company retired Stereo Records, moved stereo releases under the home label, and updated packaging accordingly to revise the Contemporary C3500/Stereo Records S7000 numbering to hybrid Contemporary M3500/S7500 scales.

Gold-on-black coloring was again used for stereo LPs on Contemporary (as well as those under Good Time Jazz and SFM). Contemporary mono variants continued as they had: yellow for jazz and green for classical. This three-color system remained unchanged through 1966.

• Flamenco 1960 •

The fourth entry in the Contemporary Popular Series deserves a bit of attention as the only Contemporary title to receive concurrent mono and stereo releases on the same label color. Remember that, going back to 1956, black/gold was the regular Popular series mono color before being stolen for Stereo Records in 1958. The stereo black/gold collided with its progenitor mono black/gold with the 1960 release of C5004/S9004 Flamenco Fenómeno.

Of note, for the two ensuing titles in the Popular Series, 5005 Latinsville (1960) and 5006 Sounds Unheard Of (1962), Contemporary opted to put their mono releases on yellow labels, perhaps opting for the lesser confusion.

mono.

stereo.

• White label promos •

• 1962 to 1973 •

Contemporary began printing dedicated white labels for promo/demo copies in 1962. Through 1966 these were mono, with the exception of 5006 Sounds Unheard Of! which saw promo deliveries in both mono and stereo.

From 1968 onward WLPs were stereo, as Contemporary had ceased releasing new titles in mono. This continued until Contemporary broke from RCA in 1973, leaving the last white label promo as S7631 I’m All Smiles.

1962

1962

1963

1964

1966

1969

1971

1972

1973

Old Green

• 1958 to 1966 •

Green remained in occasional use for classical offerings in the Contemporary Composers or Contemporary Classical Series, but separately made a late-50s (and/or early-mid 60s?) appearance on some replacement runs of the 1956 “Popular Series.”

For example, this copy of C5002 When Your Lover Has Gone:

Pearlescent Black

• late 1960s & early 70s •

Contemporary continued printing black labels in the late 1960s, but — perhaps due to a change in supplier — the surface finish and tone changed from the deep, dark, glossy black to a pearlescent matte black with a kind of blue-green twinge.

The only true new title to use this label was, seemingly, S7623 Rumasuma in 1970; however, the three volumes of Hampton Hawes’ All Night Session received their first stereo releases (S7545, 46, & 47) around 1968 on black labels as well. It seems like this color was largely reserved for reissue/catalog titles as a replacement for their old glossy blacks.

Glossy vs. pearl black

The difference in tone and surface finish was dramatic. It’s easier to photograph it an an angle.

The pearl black surface signifies a late 60s pressing at the earliest.

glossy black.

pearl black (late 60s+)

Transitional Pearl / Glossy pressings

Some pressings in this era sported glossy deep black stock on one side and pearlescent on the other, eg. this D7/D7 copy of S7568 Art Pepper + Eleven.

New Green

• late 60s & early 70s •

As black labels continued to be printed in the background, the classical green was promoted to lead color of Contemporary’s post-mono jazz catalog. New stereo jazz titles S7617 (1968) through S7629 (1971) all debuted on this green label (the possible half-exception being S7623 Rumasuma, which had at least one run on black).

1969

1970

Green Label reissues

• late 60s & early 70s •

During that same 1968-72 stretch, the green color was ported to numerous reissue titles both stereo and mono.

The application was not universal; some mono-only titles continued to use yellow labels through this period and some stereo titles continued to use glossy or pearl black. We could chalk this up in part to leftover yellow and black stock, but a few titles actually show pearl black and green labels co-existing in this era (though never, in my experience, on opposite sides of the same pressing).

late 60s

late 60s

c. 1971

c. 1973 Monarch repress using leftover green labels.

Old Green

v. New Green

Green had been in some use since 1953. How do we separate Old Green (before 1966) and New Green (after 1966)?

These late 1960s green labels were slightly paler in color than earlier green stock but still retained some gloss. Still, this is almost never going to be an important distinction. Think about it: green was reserved for mono classical and popular titles prior to 1966, which leaves little overlap with any titles that would still be in print after 1966.

I think there is just the one title. Here we see an earlier green run of Claire Austin Sings against one pressed c. 1970.

old green.

new green (late 60s+)

Concurrent Green & Pearl Black

• late 60s & early 70s •

Application of the green label was not universal; some mono-only titles continued to use yellow labels through this period and some stereo titles continued to use glossy or pearl black. We could chalk this up in part to leftover yellow and black stock— but a few titles actually show pearl black and green labels co-existing (though never, in my experience, on opposite sides of the same pressing).

Yellow labels

• 1966 to 1972 •

1966 marked the end of new mono titles on the Contemporary label, and the company took mono variants out of print around the same time (such that any titles recorded in stereo would no longer be available in mono). Soon after, the company positioned green as the lead label color for both stereo and mono reprints.

All of this meant a dramatic decrease in yellow labels catalog-wide, but a couple early mono-only recordings did indeed stay in print on the yellow label, possibly a result of leftover stock.

c. 1971 RCA 26mm ring, pre-Dynaflex

STEREO Yellow Labels

• 1972+ •

Yellow looked to be on its way out, but in 1972 a bunch of new STEREO releases were debuted on yellow labels and the color was restated as Contemporary’s primary. One of the titles was technically new though recorded ages earlier (S7630 The Way It Was!). The others were similarly old but had been previously released in mono (S7636, S7638, S7639).

Yellow became the solitary color for mono and stereo jazz pressings going forward. Some black and green labels were still waiting in inventory and were used for specific runs, but 1972 is the date floor for yellow label stereo pressings.

1972 first stereo release of You Get More Bounce

1972 first stereo release of Presenting Red Mitchell

the yellow reign

• 1970s & early 80s •

The yellow color remained dominant through the remainder of the Koenig family’s ownership. The specific yellow hue wavered a bit over that time, trending generally towards a slightly orange tone by the early 1980s.

A chunk of 1970s yellow labels suffer from faded ink, a problem which seems isolated to CBS Santa Maria pressings. Maybe heat from their presses caused the ink to fade in manufacturing… or maybe they were producing the labels themselves and their print variance was a bit wide.

c. 1973 (Monarch)

mid-late 1970s (CBS-SM)

mid-late 1970s (CBS-SM)

mid-late 70s (CBS-SM)

1976 (CBS-SM)

1977 (CBS-SM)

1979 (KM)

1980 (CBS-SM)

1982 (Wakefield)

• 1984+ (Fantasy) •

After the Fantasy acquisition in late 1984, the yellow brand color was preserved, though their yellow stock was somewhat paler than the orangey tone Contemporary had in previous years. Labels like these continued to be used on OJC Contemporary reissues into the 2020s.

Sources

“Blue Note Records: Complete Guide to the Blue Note Labels.” LondonJazzCollector, 2 Mar. 2012, londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/record-labels-guide/labelography-2/the-blue-note-labels/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.

Sacramento History Museum. “The Model 8 Linotype.” YouTube, 24 Aug. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=YAOOz_7_v9Q. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

The Museum of Printing. “Cycling of Linotype — How It Works | Linotype Legacy Series 2.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 6 Jan. 2022, youtu.be/bUvmhW_lvY8?si=jACRjsSkLH1gP7TG. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

UH Digital Media. “Linotype - a Visual Demonstration.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 12 Oct. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=5slfQizimtg. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.