vol. 1

Mono Masters

(1955 to 1958)

vol. 2

Peak Contemporary

(1958 to 1966)

vol. 3

Tone Changes

(1966 to 1984)

vol. 4

Idiosyncrasies of the Sound (1984+)

Vol. 3, Chapter 1.

The Middle & the End

The Old Sound

Back in the Saddle

Spotlight: Fake Stereo

Extensions

The John Koenig Years

Vol. 3, Chapter 2.

After 8481

The Old Sound

The 1960s proved a bit unfriendly to jazz. As the seeds of British Invasion grew to full-on Beatlemania, jazz was relegated to the sidelines and few of its old independent diskeries survived intact.

Contemporary was among that few, but essentially went into hibernation to survive. The label’s recording pace slowed to a crawl in the early 1960s, and between 1964 and 1968 barely a thimbleful of titles were squeezed out.

Bassist Ray Brown, when later interviewed for the liner notes of his 1979 record Something for Lester, remembered this difficult period and the Contemporary chief’s stalwart attitude:

When jazz took a big dip, when rock ‘n roll seemed to be taking over and the Beatles were riding high, he just never would deviate. I’m sure he could have made some changes, some accommodations, but Lester just would not be moved.

You have to admire a man like that, because I know how easy it is, not just in the record business, but in any business, to follow a trend and just do whatever is currently fashionable… I have a tremendous amount of respect for the way Lester stuck to his principles.⁽¹⁾

Important to note that Brown is only speaking to Lester’s creative tastes, because Contemporary the business did in fact make serious changes to survive. For one, it became a freelance mastering studio. As John Koenig explains:

There were guys like Jac Holzman (the founder of Elektra) and Herb Albert who were big jazz fans and fans of my father’s records. In those days, we had one of the two best stereo disk cutting systems in town. So Herb and Jac prevailed on my father to master all of their stuff. So for a long time, rather than make [money] from his records, Contemporary was surviving by doing custom disk cutting work for Elektra and A&M.⁽²⁾

So Lester contracted out the mastering system… but wasn’t eager to cut the external work himself. John again:

my father… wanted to be making his own records, not mastering other people's. So [he] cut their stuff for a while, but eventually he hired and trained Bernie Grundman to be Contemporary's mastering guy.⁽³⁾

Bernie Grundman ('66 to '68)

In 1966, Lester hired Arizonian youngster Bernie Grundman. Grundman had met Roy DuNann in Phoenix and got the hookup to meet Holzer, who then dropped his info to Lester for the open engineer job at Contemporary.

Over the next two years, Bernie ran the mastering room. Per BG:

Anybody that wanted could use Contemporary for mastering. And that was the only room that was pretty much state-of-the-art. And it had all this manipulation possibilities. So right away, everybody got word around the city because they knew Contemporary had a good reputation for sound. So, all of a sudden I started attracting all of these people. I was doing work for The Doors, Herb Alpert, Dionne Warwick, Procol Harum, you name it! ⁽⁴⁾

Meanwhile, of course, in-print Contemporary titles also needed new cuts from time to time. As noted in Vol. 2 when discussing the console, Bernie has provided valuable detail about the elaborate mastering moves he and Lester would choreograph for each Contemporary cut.⁽⁵⁾

Bernie also took on recording duties, though the stockroom studio remained arid ground. Only one title was actually captured by Bernie for the Contemporary imprint: S7617 Firebirds.

Grundman’s time at 8481 Melrose was, in the end, rather short. Having attracted the attention of Herb Alpert through his work at CR, Bernie left in 1968 to head up mastering for Herb at A&M’s new facility.⁽⁶⁾

There, Bernie would build his own name cutting countless records for A&M, Reprise, Epic… all sorts of labels across all genres. Including, eventually, Contemporary. But that came much later.

Back in the saddle (1969 to 73)

The years following Bernie’s departure saw a gradual uptick in Contemporary recordings and new releases.

Lester Koenig, student of both the old school and the avant garde, reconnected with old cats like Barney Kessel (7618), Shelly Manne (7624, 7629), and Phineas Newborn (7622) while also investing in relative new-schoolers Sonny Simmons (7623, 7625/6) and Woody Shaw (7627/8, 7632). Meanwhile he looked backwards to assemble shelved sessions into fresh LPs (7621, 7630, 7631) and made key acquisitions of old recordings from the Hifi Records catalog (7619, 7620).

Lacquers cut in this period bear some sonic resemblance to the “Peak Contemporary” cuts of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Like all Contemporary lacquers processed (plated) by the RCA Hollywood plant, the best timing data comes from the stamp styles pressed in the deadwax.

They generally look like these two below, with H stamps at 12 o’clock and small-stamp lacquer strings imprinted with a lighter touch than the late-50s embossed style. More about all that at Reading Runouts.

Spotlight: Fake Stereo

Stereo conquered mono around 1967. After this point, aging record companies faced a choice: A) to continue reissuing decade-old mono titles in stock form or B) to reprocess them into simulated two-channel presentations and benefit from fresh “stereo” marketing. Most jazz labels chose option B.

There were multiple techniques used to achieve this, all of which we now call “fake stereo.” The most horrific efforts simulated stereo space by introducing phase delay between channels. Columbia, Blue Note (post-Liberty sale), and many others dirtied themselves thus.

Other engineers who received this directive to “rechannel” found a more respectful way to achieve it. Some would simply apply EQ unequally to the two channels — one channel favoring low end and the other favoring high end — so they were able to preserve the timing and feel of the mono performance while still “spreading” sound across the stage. This is, for example, how Rudy Van Gelder approached re-channeling titles for Prestige.

Contemporary mostly avoided the fake stereo craze… with one exception.

First, for context. Vis a vis mono/stereo questions, there were three types of Contemporary recordings in the catalog:

those recorded in mono only (pre-July 1956)

those recorded simultaneously to mono AND stereo tape (July 1956 to c. Nov. 1958)

those recorded to stereo tape ONLY (Nov. 1958 +)

After 1966, the first category would continue to be reissued in good old mono, no fakery or reprocessing.

The second and third categories were then lumped together, as any album recorded in stereo would only receive reissue treatment in stereo from now on. So the dedicated mono mixes from 1956-1958 were shelved indefinitely.

C3536 Concerto for Clarinet & Combo was unique, however, straggling multiple categories. Four of its six tracks were recorded in July 1957 to stereo and mono tape machines, but the last two were captured back in December 1955 in mono only.

So two-thirds of the album existed in true stereo, but a stereo master couldn’t be assembled in full. Les Koenig clearly favored stereo mixes where available, so it’s little wonder that the title did eventually fall on the stereo side, when circa 1972 or 73 Les Koenig cut stereo lacquers for S7536.

The first four tracks were true stereo, of course, with the final two “electronically rechanneled.” Lester could have left them alone in mono — and perhaps would have, if left unsatisfied by the experiment. But the D1 first lacquer made it to production and the result is not terrible, really, with tastefully applied “unequal EQ.”

Listen below to the original mono mixes vs. the rechanneled stereo presentations.

Extensions

As dissected in Reading Runouts Pt. 2, Contemporary processed its lacquers (and pressed records) at RCA Hollywood until 1973, at which point they took their business to Monarch. This relationship lasted only a year or two, so Monarch-processed lacquers were few in number.

That said, the plant did handle and repress a buttload of Contemporary’s old RCA parts, and these can be identified by the presence of BOTH the RCA “H” and Monarch “MR” stamps in runouts, with the former vigorously crossed out.

The far more exclusive club is for 8481 Melrose cuts electroplated by Monarch. The tight 1973-74 contract timeframe offers very localized timing data for specific 1973-1974 masterings.

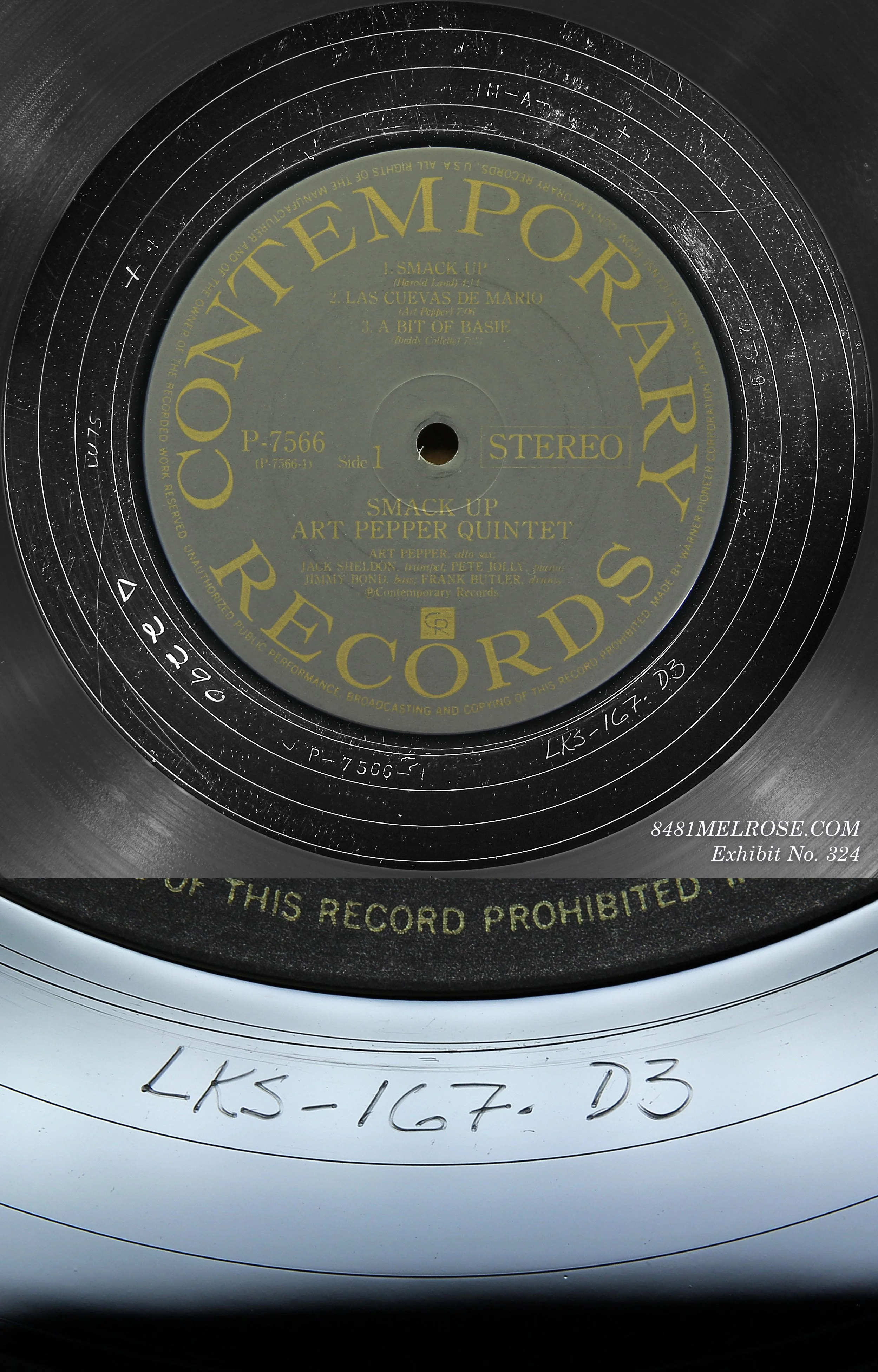

These Monarch-era cuts have etched matrices with Monarch delta codes and MR stamps, and they show NO lineage back to RCA Hollywood (ie. they do NOT have have a crossed out H stamp). The lacquer strings are very lightly etched and photographing them is a huge pain in the ass… but I tried:

Spotlight:

S7549 The Arrival of Victor Feldman

To checkpoint sound in this Monarch period, you need an apples-to-apples comparison to an earlier era. These are rare because a title with metal replenished in, say, 1968 or 1971 would statistically be unlikely to need another replenish in 1973. Nonetheless a couple examples exist, like The Arrival of Victor Feldman.

One of the reasons to focus on S7549 is that:

1) this is a freakin incredible album, 2) I actually own the versions necessary for a comparison, 3) it’s a super extended recording with Feldman’s insistent vibraphone cutting an intricate top end, and 4) the title has consistent checkpoints cut in the late 1960s, 1973, and mid-late 1970s.

The original stereo release arrived in the late 1960s. It was a green label RCA Hollywood deep groove press using lacquers cut around that time frame. Side A is LKS-103-D2 and Side B is LKS-104-D3:

When Contemporary moved pressing to Monarch (1973), a new side A was cut: LKS 103 D3. The original late 1960s metal for side B (LKS 104 D3) perservered:

Subsequent re-cuts in the mid-late 1970s provided new metal for both sides, LKS 103 D4 and LKS 104 D4:

So we can use this title to nail down identifiers associated with the next era of lacquer cuts:

Documentation handled, hear the opening track “Serpent’s Tooth” across these three lacquer generations:

S7607 Intensity

“Come Rain or Come Shine”

Let’s visit another title, S7607 Intensity, using third track “Come Rain or Come Shine.” Like The Arrival of Victor Feldman, this LP offers us three checkpoints into the evolution of the cutting room:

The first example is off the original 1963 stereo press, the LKS 247 D2 cut.

The second is a late 1960s stereo cut, LKS 247 D3.

The third is the mid-to-late 1970s stereo cut, LKS 247 D4.

These are just a few comparisons, but repeat this a few dozen times and you’ll develop a pretty clear picture. Later cuts out of 8481 tend to deliver more extension and tighter detail at the extremes— advancements owed, reportedly, to developments in the Westrex cutting head design.

Those advancements sound good in principle, right? Yes— but like focus in a photograph, neutrality isn’t everything. Neither is frequency extension. Should every title invariably sound better with more “advanced” cutting tech? Certainly the palette of colors grows, but the old colors also change hue.

Change was meanwhile multidimensional and decidedly human, as Contemporary’s on-the-fly adjustments to reverb, panning, and EQ clearly evolved with new technology and changing tastes. History, personnel, and equipment all figured into this equation of sound, and you can’t judge one without balancing the rest.

Richard Simpson

Like Bernie Grundman was hired to master for Lester in the 60s, it’s plausible that other engineers moonlighted through Contemporary in the following years. Info is a little bit inconsistent, but one checkpoint we DO know is Lester hired Richard Simpson in 1977.

Simpson had started his mastering career in New York, working at RCA Studios where his father Bob Simpson was a well-established recording engineer. In the early 1970s, Richard had transferred to the label’s Hollywood studios, working there until January 1977 when the facility shuttered. That’s when Les Koenig gave him a ring.⁽⁷⁾

The next ten months he spent cutting new lacquers for the Contemporary/GTJ catalogs.⁽⁸⁾

How to identify his work at Contemporary? I’m not sure. I’ve done plenty of research on that era (Reading Runouts Pt. 2) but I’m unclear of any identifiers which separate his cuts from those made by other engineers @ 8481 in the surrounding years.

The John Koenig years

In August 1976, Lester Koenig brought Hampton Hawes back to the studio and captured tracks for what would eventually become S7637 Hampton Hawes at the Piano. Lester was still busy preparing the LP when the pianist died the following May, unexpectedly, at 48.

The loss hit Lester hard. Among all musicians, John Koenig has said, Hamp was his father’s “best friend.”⁽⁹⁾ Their final session retreated to the shelf unfinished.

A few months later, Les lost another old friend and colleague in Jack Lewerke. Jack had joined GTJ as general manager back in 1950, and the ensuing decade saw him and Lester link up on multiple ventures such as California Record Distributors and Interdisc.⁽¹⁰⁾ They remained close friends throughout the years. Lester served as pallbearer at the funeral.⁽¹¹⁾

Later that week, Lester fell ill and was rushed to hospital. Two days later, November 21, he died. He was 59.

***

The outpouring from artists and colleagues was immediate, with remembrances hailing Lester as a bold enterpriser, a perfectionist, and a warm soft-spoken personality who valued relationships and earned others’ respect.

Amidst the obituaries, though, there remained the question of business:

Who would run the Contemporary operation was not clear. Koenig was the company, although he had several employees. “We’re going to carry on,” his wife says.

— Billboard, 12/3/77⁽¹¹⁾

Ownership of the label soon fell to Lester’s two eldest children, John and Victoria, from his previous marriage to Catharine Heerman. In early 1978, John Koenig took the lead chair at 8481 Melrose.

1950 Turk Murphy recordings memorialize the birth of John.

Lester & John Koenig in later years. Photo courtesy of John Koenig, provided to JazzTimes.⁽¹²⁾

John was young but the natural successor. He’d grown up around 8481, trained to use the cutting lathe as a teenager, and after college spent several years working for the label and gathering producing credits on Contemporary LPs. It’s in that period he actually recruited trumpeter Woody Shaw to become a Contemporary leader.

Despite that jumpstart into producing and A&R, though, John was a musician at heart and an ascendant talent on the cello. He left home in 1976 for a spot at the Jerusalem Music Center and one year later joined the Swedish Radio Symphony in Stockholm. He was only six months into that prestigious gig when he got the news his father had died.⁽¹³⁾

So he returned to Los Angeles and expected to spend a year handling estate affairs before returning to the cello in Europe. That year came and went as he settled into the head chair at Contemporary prepping his father’s final sessions for release. Los Angeles became home once more, as his duties for the label supplanted his dreams of pursuing the cello. For seven years, he ran Contemporary as both steward of the old tapes and purveyor of new music.

From the years 1978 to 1980, John manned the lathe at 8481:

During the three years we remained at our original facility on Melrose Place, we had to replace metal parts on our catalogue to keep our titles in print. It was a constant thing. I myself cut hundreds of sides.

— John Koenig, via Myles B. Astor⁽³⁾

Stepping back to 1977, remember Richard Simpson had been on Contemporary’s staff running the mastering room. So, given Lester’s death and John’s accession around the top of 1978, an open question remains whether Simpson and John Koenig shared duties through any period or if there was a hard transition. Simpson has commented that he “stayed on for awhile helping… John keep the label going until he decided to sell the label.” ⁽⁷⁾ I’m unclear what exactly this means, and if this speaks to a few months, a year, or multiple years.

My guess would be months. Simpson soon started up his own mastering studio, The Reference Point, filed for incorporation in California in April 1978.

The replacement amps:

HAECO GW-120A monoblocks (1978 to 1980)

When John took over the label, the original Contemporary cutting amp was two decades old. Its co-creator Roy DuNann, now a maintenance engineer for A&M, made routine drives over to Contemporary to band-aid whatever problems his and Holzer’s lovechild would inevitably develop.⁽¹⁴⁾

As the amp’s breakdowns became more frequent, though, Roy encouraged John to cut to cord. He connected young Koenig with Philadelphia-based producer/engineer Frank Virtue, who was packing up his studio selling off a pair of cutting amps.⁽³⁾ These were GW-120A monoblocks — still HAECO, still vintage, but younger and more polished than ol’ HAECO #1, which was finally put to pasture.

The GW-120A amps would put in just a couple years’ service at 8481, but their story continued after that. These tube units remain in service to this day, powering a Westrex head at Bernie Grundman Mastering in Los Angeles. Several changes and refurbishments have been implemented through the decades, but Bernie and partner Chris Bellman have used the pair to cut many of the greatest lacquers of the past thirty years for Classic Records, Analogue Productions, ORG, Impex, and the major rightsholders.

The tube situation at Bernie Grundman mastering (The Audiophile Man)

the GW-120A amps (Mono & Stereo)

In recent years the 120As have come full circle, cutting Contemporary titles for Chad Kassem and Craft’s Acoustic Sounds Series, which began life in 2015 as an Analogue Productions series inclusive of John Koenig.

a 2015 video with Kassem, Grundman, and Koenig shows the HAECO GW-120As in context.

1980 ushered in

at least two new changes for Contemporary. First, John Koenig began releasing new recordings made under his own supervision, with new 14000 series numbering. Second, Contemporary vacated the offices, studio, and cutting room at 8481 Melrose.⁽³⁾⁽¹⁵⁾

These two things happening in concert poses an obvious question: who’s going to cut the new 14000 series?

Bernie Grundman @ A&M Studios

In more than a decade atop A&M’s mastering shop, Bernie Grundman had built a stellar personal reputation among popular artists. His reach made his start at Contemporary look humble, but John Koenig — who’d learned mastering in symmetric fashion to Bernie⁽¹⁶⁾ — trusted the common instincts they’d both learned at 8481.

So he hired Bernie to cut his new titles. In fact, runouts indicate he hired Bernie prior the shuttering of Contemporary’s studio, as inaugural title 14001 Cables’ Vision shows SLM job code △232, pointing to early 1980 while reissue lacquers were still being cut at 8481 (see Reading Runouts Pt. 2).

The 14000 series got ten titles deep by 1983, and nine of those credit Bernie with Disc Mastering:

14001 Cables' Vision

14004 Lunch in L.A.

Look closely at Bernie’s etchings and see the distinct style he’s carried on to this day. A style most noticable in his characteristic “2” which look like an upside down 5, which we might as well call “the Bern”:

14002 Sonic Text, side 1

14007 Rain Forest, side 2

14010 Peter Erskine, side 1

Lacquer “A” numbers

Some of these 14000 series sides have the addition of an “A” suffix after the lacquer D number. For example, below are two alternate cuts for the same side of 14005 Peaceful Heart, Gentle Spirit. One is D1 (the test press), the other D1A (the commercial release), and at close glance we can see these are separate lacquers inscribed independently and processed by two different plants, CBS Santa Maria (D1) and SLM (D1A).

The runouts and track widths are identical between these two cuts. So logic would dictate these are duplicate lacquers cut either a) in tandem on multiple lathes or b) in succession in the same session using the same or similar settings.

The Reissue Mysteries

What about recuts of old sides? Metal for in-print titles would need replenishing from time to time— which meant lacquers needed to be cut. With new titles going to Bernie, one might assume the label’s reissues would fall to him as well. The truth seems more complicated.

Let’s isolate this era of lacquers using plating info and lead-out LPI, as we discussed in the previous chapter.

1980 to 1984 (post-8481 Melrose) reissue lacquers will have SLM delta codes starting in the mid-300s, with some overlap during the transition. Those below are confirmably post-8481 Melrose:

As is discussed in some more detail in Reading Runouts Pt. 2, lead-out LPI can be used (with some nuance) to distinguish 1980 Melrose Place cuts from the post-Melrose cuts that came immediately afterwards.

This proves critical for at least one title, C3532 Benny Golson’s New York Scene. This album was cut for reissue c. 1979/80 at 8481 Melrose, and the two sides (LKL-12-161-D6 and LKL-12-162-D11) assigned SLM codes △50 and △50-X, respectively.

Subsequent to that, a new side 2 was cut, LKL-12-162-D12A, but was still assigned the same delta code as the previous side 2 lacquer (△50-X). Exposing the SLM codes as true JOB codes, rather than lacquer-specific.

So the delta code becomes useless for dating that new lacquer. And in comes lead-out LPI to help us out.

Below see these two different lacquer generations with significantly tighter lead-outs:

Who cut reissues from 1980 to 84?

For a long time, I assumed these post-8481 reissue lacquers were cut by Bernie. Why not? John Koenig trusted Bernie’s instincts with his new titles, and there was no working engineer with a better sense of the old Contemporary tapes.

But… the runout etchings on these reissues don’t back up the hypothesis. The runouts look consistently different from the known handwriting of Bernie, who consistently etched his own runouts in this period.

Remember how among the ten 14000 series titles, only nine are credited to Bernie? The tenth and uncredited title is 14006 Relaxin at Camarillo… which just so happens to show the other etching style I’m talking about:

This confident curvature tracing the arc of tight tight lead outs is exactly what we see on reissues of the period. And clearly NOT the script seen on the nine titles credited to Bernie G.

But remember that Bernie was cutting some “A” lacquers for the 14000 series… and there are plenty of “A” lacquers which appear among these reissue cuts as well:

Again these A cuts seem to be tandem versions to their non-A counterparts, as seen on the two downstream expressions below, one a 1982 Japanese press using imported US metal and the other a post-Koenig Fantasy OJC:

So there are “A” lacquers over there on new titles and “A” lacquers over here on reissues. Shouldn’t that show they’re cut by the same dude?

No. It’s clear that Contemporary was routinely ordering duplicate lacquers in this era, but our best evidence — actually listening to these reissue sides — points away from Bernie or any 8481 engineer as their author. The old notes for reverb and EQ seem to figure not all that much — or not at all — into their sound.

So who in the hell cut these LPs?

Long story short, I don’t know. Other possibilities abound: these could have been cut by someone else at A&M, the Sheffield Labs engineers (who cut many D2D LPs on their quartet of tandem lathes), Richard Simpson at his new shop, John Koenig at another studio, the folks at Studio Masters who get some shoutouts on CR LPs, Richard C. Gore (an Elektra engineer who got special thanks on Relaxin at Camarillo), or some unnamed engineer at the tape storage facility wherever the Contemporary masters were stored…???

None of these guesses convincingly checks the box. I’ve spent a long time trying to research this and encountered dead end after dead end. I’ve dug through Amanda McBroom and John Denver records looking for matching inscription styles to somehow, miraculously, find an answer. I simply don’t have it. I so wanted to solve it on my own, but until I can connect with someone like John Koenig, I’ll call this person Mystery Engineer(s).

Putting the search to bed for now, we need to touch again on sound. Most of these early 1980s reissues sound absurdly good. These are probably the closest we will ever get to experiencing most of these master tapes…

… in the positive and occasionally negative sense. While the majority of the cuts are stunning, a few (S7530, S7532, S7539, S7600) sound a bit unbalanced, toppy, maybe even bass-light. And, again— they seem to sport no outboard reverb. But whatever system cut these LPs was mint, with a top end so clean it makes me seriously believe that cutting tech peaked 40 years ago. Art Pepper +11, Maggie’s Back In Town, Gettin’ Together, Pal Joey… the vast majority of Contemporary reissues cut in this era are simply faultless.

But how do they compare with the stuff cut years earlier at 8481? At the very least, they expose by contrast how critical mastering equipment and editorial mastering notes were to delivering the 8481 system’s specific sound. And that comparison is a happy activity, one in which two vastly different cutting systems — and what sounds like diametrically opposed levels of active adjustment throughout the cut — both create valuable and engaging experiences. Just because there are a hundred ways to get something wrong doesn’t mean there is only one way to get it right.

Sources:

Jazz Discography Project. “Contemporary Records Discography Project.” Jazz Discography Project, www.jazzdisco.org/contemporary-records/. Accessed 2020.

(1) Feather, Leonard. Liner notes. Something for Lester. Ray Brown. Contemporary Records, Oct. 1978. Vinyl.

(2) The Jake Feinberg Show. “The John Koenig Interview.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 9 Apr. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=yNM-YR6Afy4&t=4565s. Accessed 2023.

(3) Astor, Myles B. Comment on “Rudy Van Gelder versus Roy DuNann.” Audionirvana, 2 Mar. 2020, https://www.audionirvana.org/forum/music/audiophile-issues-reissues/132338-rudy-van-gelder-versus-roy-dunann#post132399.

(4) Grundman, Bernie. “A Talk with Vinyl Mastering Engineer Bernie Grundman – the Secrets Interview.” Secrets of Home Theater and High Fidelity, interview by Carlo Lo Raso, 29 Sept. 2022, hometheaterhifi.com/features/factory-tours-interviews/a-talk-with-bernie-grundman-the-secrets-interview/. Accessed 2023.

(5) Acoustic Sounds. “Contemporary Records Mastering Session with Bernie Grundman, Chad Kassem, and John Koenig.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 13 May 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=LgbPnzDmYEU. Accessed 2022.

(6) Acoustic Sounds. “Bernie Grundman and Chad Kassem Discuss the Upcoming Contemporary Series.” YouTube, 8 Apr. 2022, youtu.be/a7tUfTL2U_Q?si=KCz04rXD7A4N5PhP. Accessed 2022.

(7) Simpson, Richard. Comment on “Collector’s Guide to Contemporary Records Part I.” LondonJazzCollector, 20 Jul. 2019, https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/2016/01/05/collectors-guide-to-contemporary-records/#comment-66135

(8) Simpson, Richard. Comment on “Collector’s Guide to Contemporary Records Part I.” LondonJazzCollector, 03 Oct. 2021, https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/2016/01/05/collectors-guide-to-contemporary-records/#comment-82815

(9) Kevin van den Elzen. “West Coast Jazz Hour #40 with John Koenig.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 31 Aug. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbcYtNB2e2w. Accessed 2023.

(10) “Heart Attack Claims Independent California Distrib Jack Lewerke.” Billboard, vol. 89, no. 47, Nov. 1977, p. 10. Google Books.

(11) “Les Koenig, Label Owner, Dies of Heart Attack in Los Angeles.” Billboard, vol. 89, no. 48, Dec. 1977, p. 15. Google Books.

(12) Amorosi, A. D. “The Sound of Contemporary Records.” JazzTimes, 8 Apr. 2022, jazztimes.com/features/profiles/the-sound-of-contemporary-records/. Accessed 12 Nov. 2024.

(13) Koenig, John. “Membership Spotlight: John Koenig.” Cello.org, 2004, www.cello.org/Newsletter/MemberSpot/koenig.htm. Accessed 2023.

(14) Acoustic Sounds. “An Interview with John Koenig, Former President of Contemporary Records.” YouTube, YouTube Video, 22 Apr. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAsuVLN_lyo. Accessed 2022.

(15) Bruil, Rudolf A. “History of Contemporary Records.” Sound Fountain, 2010, www.soundfountain.com/contemporary/contemporary.html. Accessed 2019.

(16) “‘Pressed for All Time,’ Vol. 9 — John Koenig, Sonny Rollins, and William Claxton Talk about Rollins’ 1957 Album Way out West.” Jerry Jazz Musician, Aug. 2016, www.jerryjazzmusician.com/pressed-for-all-time-vol-9-john-koenig-sonny-rollins-and-william-claxton-talk-about-rollins-1957-album-way-out-west/. Accessed 2023. (Excerpt from book “Pressed For All Time” by Jarrett, Michael.)

Amorosi, A. D. “The Sound of Contemporary Records.” JazzTimes, 8 Apr. 2022, jazztimes.com/features/profiles/the-sound-of-contemporary-records/. Accessed 12 Nov. 2024.