Reading Runouts, Pt. 2

In part 1, we covered the plating process in general before digging into the stamp styles and timing cues of Contemporary’s original 12-inch plating partner RCA Hollywood.

Part 2 picks up in early 1973 when Contemporary parted from RCA and took its business south to Monarch Record Manufacturing.

Part 1

00. Plating Basics

01. RCA Hollywood

Part 2

02. Monarch Rec. Mfg. Co.

03. CBS Santa Maria

04. SLM & the end of 8481

05. Wakefield Mfg.

Monarch (1973-74)

The exit from RCA appears to have happened in the first half of 1973. Contemporary moved to Monarch Record Manufacturing Company, a prolific and now-legendary Crenshaw plant which, like RCA, left indelible marks in the metalwork. Those marks — detritus, if you will — is less tidy than RCA’s but ultimately much more insightful vis a vis timing and decision-making.

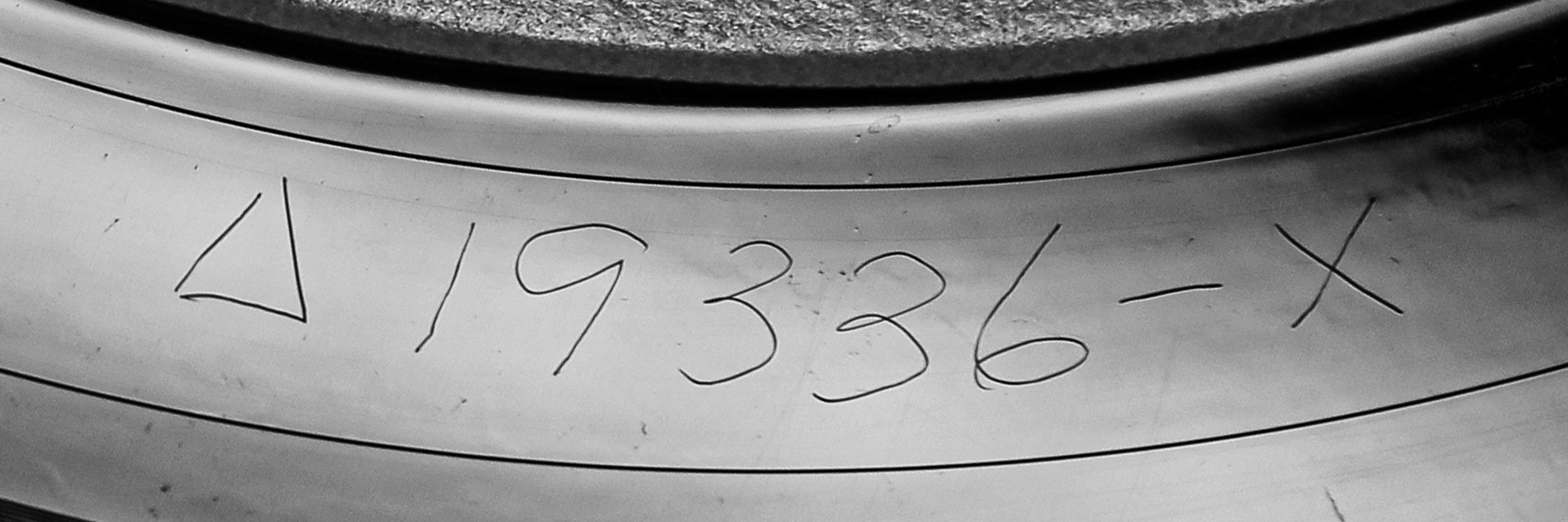

Monarch Delta codes (Δ1xxxx, Δ1xxxx-X)

Monarch ran on job codes, and job codes are beautiful things. These were intended to keep track of metal parts in the factory and would be inscribed directly into the runouts. Any part could, I suppose, be identified by reading its code and looking it up in the company records. It’s a simple but effective system suited to the work.

These codes were assigned sequentially. By the time Contemporary moved to Monarch, the plant had eclipsed 17000. Like many plants in this era and beyond, these codes used a delta character as signifier:

LKS-233-D2 (S7545, side 1) All Night Session, Vol. 1

Given the consistent assignment of these codes across ALL jobs at the plant, we just need a large sample set of Monarch pressings (preferably new recordings off any label) to estimate the year for a specific code.

Here Discogs comes in handy, as tens of thousands of Monarch plating jobs are identified there. Assuming the site doesn’t collapse under its design bloat (like I’m one to talk), you can organize by catalog number and see these in the sequence their codes were assigned:

Alternately, if you’re feeling less masochistic, you can reference Friktek’s PDF database of Monarch titles which has been circulating among internet audiophiles for years.

Now we get to Contemporary. In 1973 they schlepped their RCA metal to Monarch, whose staff got to work readying that metal for new runs. As part of that process, they assigned each side a job code and inscribed it directly into the part. The standard practice, if both sides of a title were re-processed at the same time, was to apply a delta code to the A side and the same code with a -X suffix on the B side. Thus we start to find codes like these on Contemporary LPs.

LKS.99.D3 (S7551, side 1) Something Else!!!!

LKS 100 D3 (S7551, side 2) Something Else!!!!

LKS.59.D2 (S7555, side 1) Jazz Giant

LKS.60.D2 (S7555, side 2) Jazz Giant

In other cases, one stamper would have a much higher job code than the opposite side. This was uncommon to see when both sides were RCA represses, but if one side of a title was a repress and the other side a newly cut lacquer, they invariably had different codes.

The details are not that important; the important takeaway is that delta codes speak directly to the time of plating and/or cataloging by Monarch. So, looking again at Monarch’s Discogs listings, we can insert the delta codes assigned to Contemporary plates and get an accurate timeframe for when each of those plates was replated or put into service.

Below is an (incomplete) accounting of Monarch delta codes assigned to Contemporary/Good Time Jazz jobs and the rough timing these codes suggest:

The MR stamp & other indicators

In addition to their job codes, Monarch’s custom stamp graces most of the metal they touched. Though not as minimal as RCA’s H, the Monarch stamp shows more modern flair, stylizing the MR characters inside a tiny circle.

This MR reads left-to-right if the stamp was pressed into a lacquer or mother, and it’s not uncommon to find it mirrored backwards— a likely indication it was punched into a stamper or master.

You might find some additional Monarch detritus. The scratchings below likely refer to mother/stamper numbers or labels or whatever but they’re not useful enough to focus on:

(1) added to the end of a Delta code.

2 belatedly added alongside the MR.

REPL appearing after a lacquer string.

the crossed-out H

On every Monarch re-use of RCA metal, the original Hollywood “H” is crossed out, and kind of violently. I’m curious if RCA did this themselves to the entire batch of metal before handing over custody, because some foreign 1960s pressings show a similarly hand-cancelled H.

Typical cancellation on Monarch replate.

Another Monarch.

1960s Dutch repress.

1973-1974 MONARCH RE-PLATES

of Contemporary RCA Hollywood metal

Collecting our identifiers, we can fully profile Monarch’s reuse or replates of Contemporary’s RCA metal:

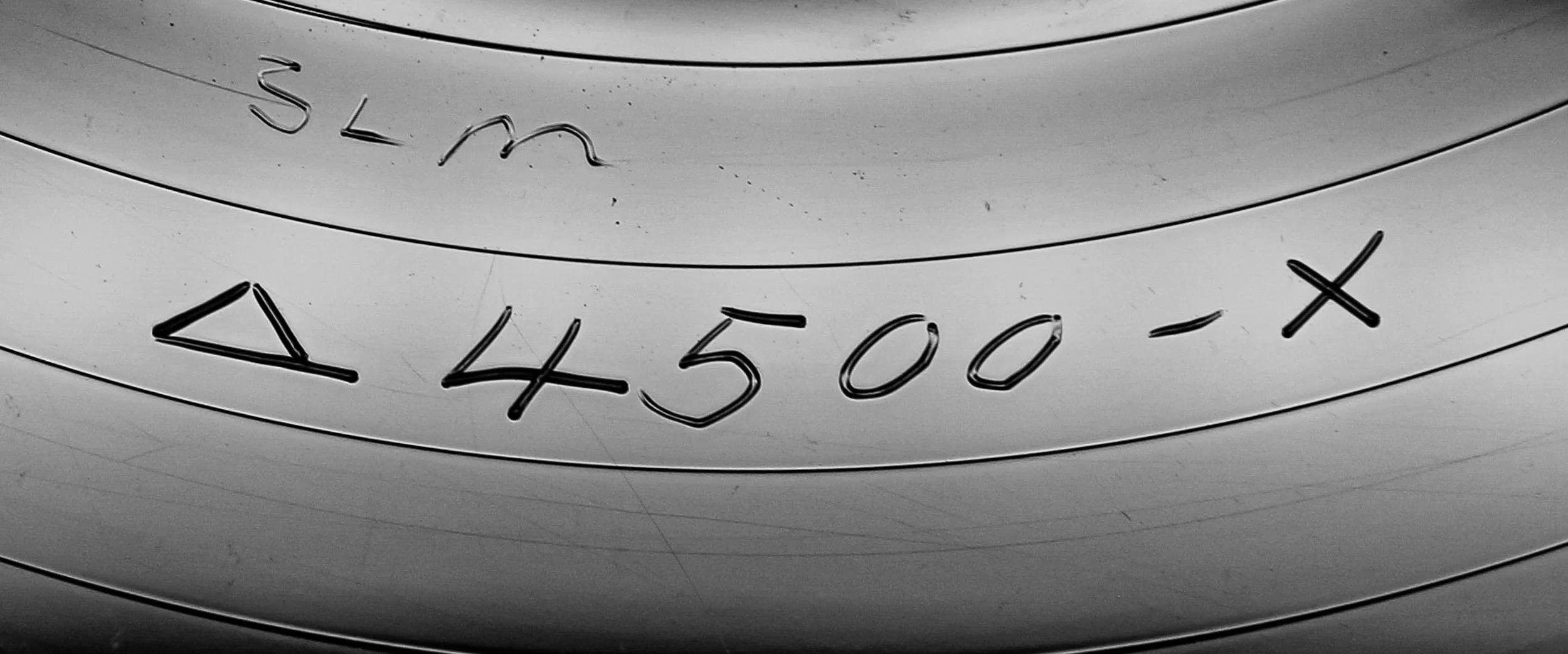

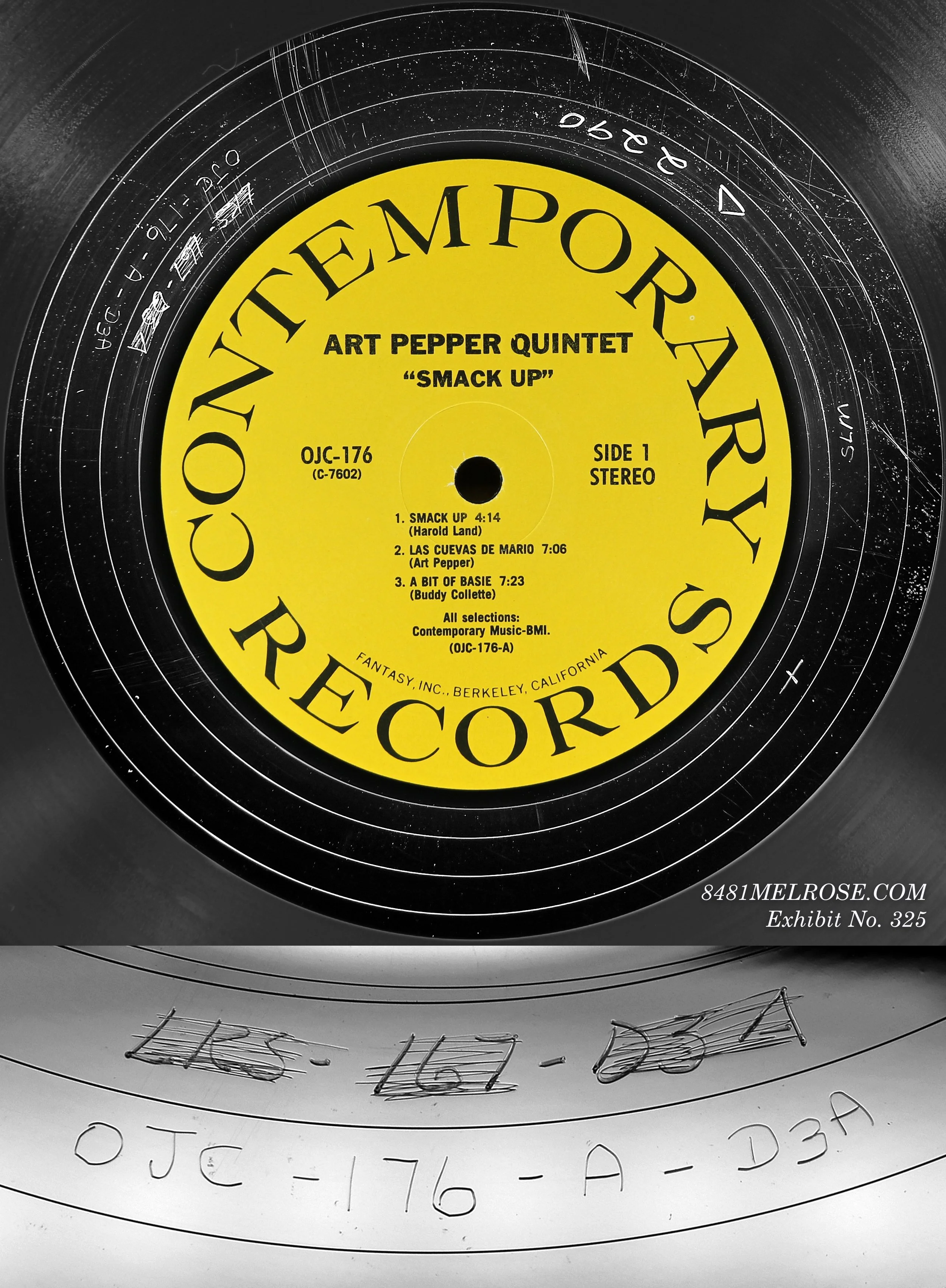

S7602 Smack Up!

C3552 Benny Golson's New York Scene

While repressing the old metal, Monarch also processed any new Contemporary lacquers. In the end, though, only one new Contemporary title was was released in this timeframe: S7632 Song of Songs, released in 1973. The title’s processing yielded something new for Contemporary: a fully etched lacquer string.

The processing marks then provide a rubric for identifying replacement lacquers cut in this period:

1973-1974 NEW TITLE &

REPLACEMENT LACQUERS

New lacquers processed @ MR

All lacquers cut during the Monarch period exhibit etched runouts like Song of Songs. Consistent with a short timeframe, there seem to have been only a handful:

New title, S7632 (1973) Song of Songs, Side 1

New title, S7632 (1973) Song of Songs, Side 2

Replacement, S7549 The Arrival of Victor Feldman, side 1

Replacement, C3515 This Is Hampton Hawes, Side 2

The Monarch partnership was ultimately short-lived, lasting something like a year and a half. As 1974 turned to 1975, the leftover metal — still bearing Monarch’s runout annotations — was passed to CBS Santa Maria.

CBS Santa Maria (1975-81)

Having operated in Hollywood since the 1930s, Columbia Records moved up the 101 to Santa Maria in 1962. The major pressed its house titles there for the next two decades while also soliciting business from independents like Contemporary, who hired the facility in 1974.

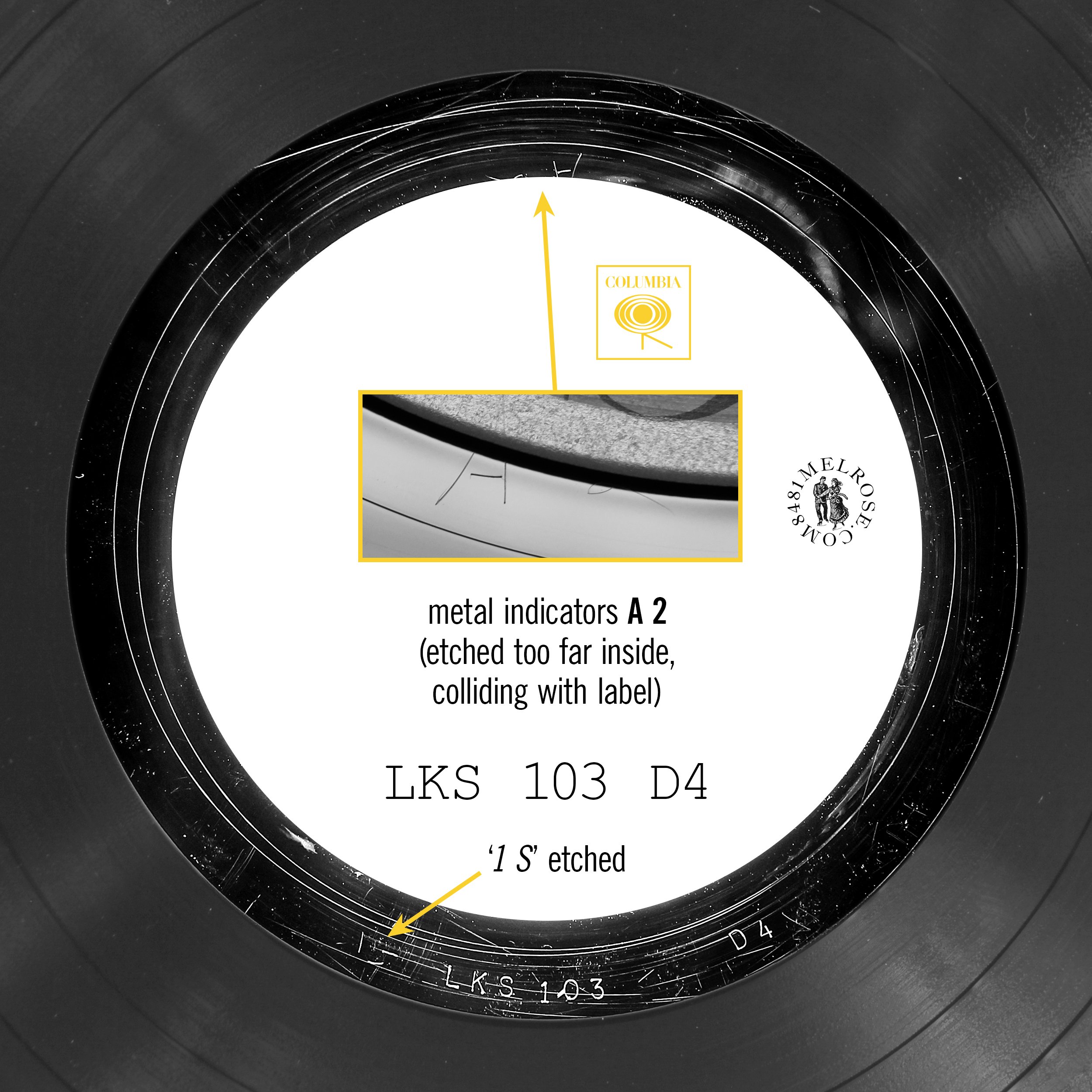

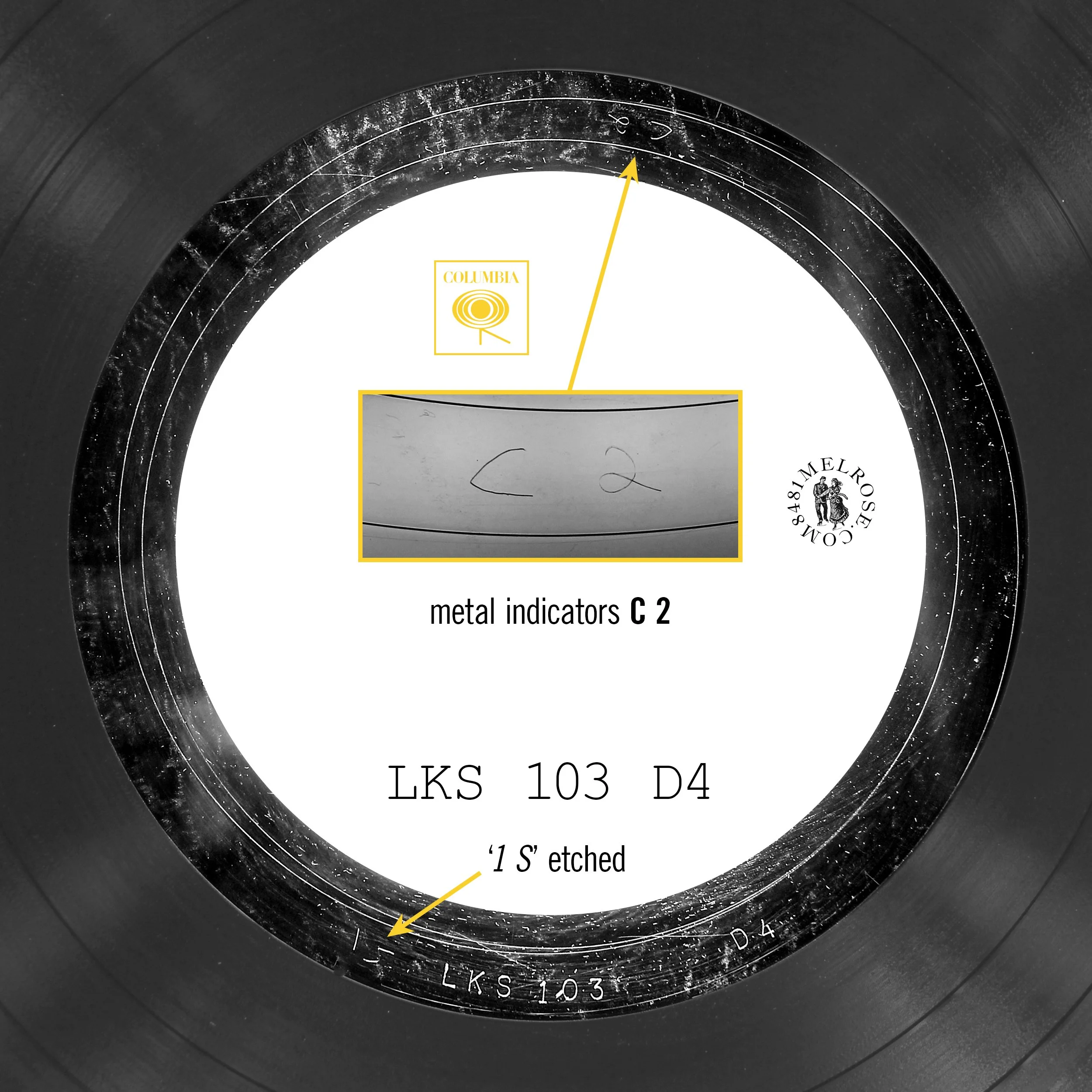

The Santa Maria S and indicators

CBS-processed Contempoary lacquers can be identified by their tracking identifiers in the runouts. The most noticeable being the informal ‘S’ etched just clockwise of the lacquer string, sometimes with a number 1 or 2 next to it. Notice, in the two examples below, that the S is constant and the number changes. A mother indicator, perhaps?

1 S LKS 104 D4

S 2 inscription LKS 104 D4 (equivalent metal)

An inscribed letter-number pair (like A2 or B1) likely also point to part numbers.

1975-1981 CBS-SM REPLATES

of RCA and/or Monarch metal

Despite having routine markers in the toolbox, CBS often reused Contemporary’s old metal without leaving any mark whatsoever. They also left Monarch’s decisive trackers alone, which creates some collector confusion because CBS’s 69mm pressing ring is only ~4mm smaller than Monarch’s (see Pressing History).

In some cases you will find CBS plating marks on represses, but don’t expect consistency. If you’re trying to determine pressing plant look at the pressing rings, not the runouts.

S7554 (CBS reuse/replate) Portrait of Art Farmer

S7617 (CBS reuse/replate) Firebirds

Return of the stamps

Lacquer string style can help us infer details about timing and mastering within the CBS period. In 1975, stamped lacquer strings made a Contemporary comeback. It seems like Lester & co, perhaps nostalgic for RCA’s clean stamped aesthetic, started stamping runouts themselves.

These stamps are close in size to the RCA “large” stamps (1960-63) but reliably different at close glance.

1975~1977 NEW TITLES &

REPLACEMENT LACQUERS

New lacquers processed @ CBS-SM

New Title, S7635 (1975-76) Straight Ahead

New Title, S7638 (1976-77) The Trip

Replacement, S7568 Art Pepper +11

Replacement, S7599 Checkmate

~1978 REPLACEMENT LACQUERS

New lacquers processed @ CBS-SM

After John Koenig took ownership of the label at the end of 1977, etched lacquer strings began appearing on Contemporary lacquers, with at least one distinct handwriting style recurring between several cuts.

I believe these specific etched-string/CBS-processed lacquers fall in 1978 prior to the SLM relationship which started at the end of 78 or beginning of 79.

This is a bit of a tentative theory based on a lot of small corroborating evidences, rather than any one giveaway.

Replacement, S7554 Portrait of Art Farmer

Replacement, S7569 Tomorrow is the Question!

1980 NEW TITLES, 14000 series

Some new lacquers processed @ CBS-SM

When John Koenig launched the 14000 series in 1980, he’d already engaged plating firm SLM to process lacquers going forward. SLM was indeed involved in most of the released sides, however some of these new title lacquers (cut by Bernie Grundman @ A&M) were sent directly to CBS and processed there while equivalent (tandem?) copies of those lacquers were sent to SLM.

This might be a bit confusing. We’ll revisit this in the next section when talking about SLM, but for now, two 14000 examples of CBS lacquer processing are below.

14004 Lunch In L.A. LKS 364 D2 (Grundman)

14005 Peaceful Heart, Gentle Spirit LKS 368 D1 (Grundman)

BG’s etching style, seen above, is distinctive as hell and in the deadwax of thousands of LPs over more than five decades. Once you’ve seen it a hundred times you get good at identifying it. Not that it usually requires investigation; in the case of these new Contemporary titles, Bernie’s name was simply printed on the jacket.

Sheffield Lab Matrix

& the end of 8481 (1979-84)

After the 1970s oil crisis caused vinyl puck quality and weight to dip, audiophile labels like Mobile Fidelity and Nautilus reinvigorated “Hi-fi” marketing in new clothing that, in part, highlighted pressing quality. They sought to press LPs outside the US where production standards were higher and less mangled by cost-cutting. But this was about more than just plastic. It was also about plating.

“The expansion of the premium-priced direct-disk and audiophile recording market, coupled with better playback equipment that brings out the ‘worst’ in the typical U.S.-produced LP, has brought what is claimed as the first European state-of-the-art plating facility to America.

— “Europadisk Makes Plating Waves,” Stephen Traiman, Billboard, Dec. 17, 1977

A handful of dedicated plating firms sprung up in the United States with the goal of extricating the delicate precision of plating from the sweaty manufacturing of pressing plant floors.

Among these was New York-based Europadisk, which in its 1977 statement of purpose explained that “electroforming of record production parts is a highly complex process, demanding extremely tight control of all operational parameters as well as the maintenance of a contaminant-free environment.” In contrast with “heavy industry” pressing operations, EPD claimed plating “better suited to a laboratory.” They placed consumer playback problems at the feet of quality control, as many plants tolerated “a surprisingly wide range of errors while still producing a part which is deemed 'useable.’”

Whether absolute truth or part marketing speech, these claims helped plating facilities attract monster business over the next decade. And the most prominent west coast plating plant was Sheffield Lab Matrix.

SLM was launched by Doug Sax and Richard Doss in 1979 as sister business to direct-to-disk label Sheffield Lab. With regards to the Contemporary story, SLM figures heavily in its final chapters.

Contemporary hired SLM, based in Santa Monica, at the beginning of 1979 to handle processing of new lacquers. SLM didn’t touch Contemporary’s pre-existing metal which remained — for now — with CBS Santa Maria.

To track a workflow that inherently passed the baton to a separate pressing plant, SLM clearly marked and cataloged metal parts. Which is great for us.

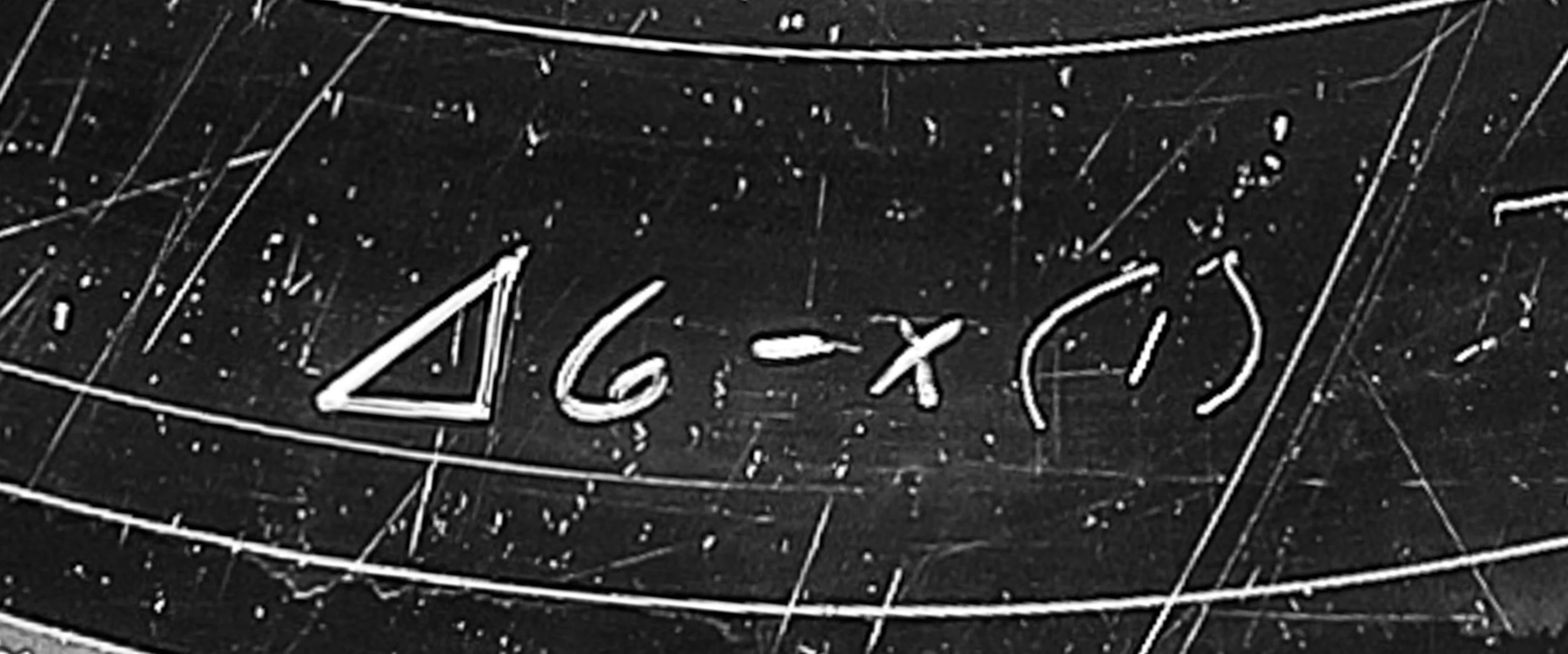

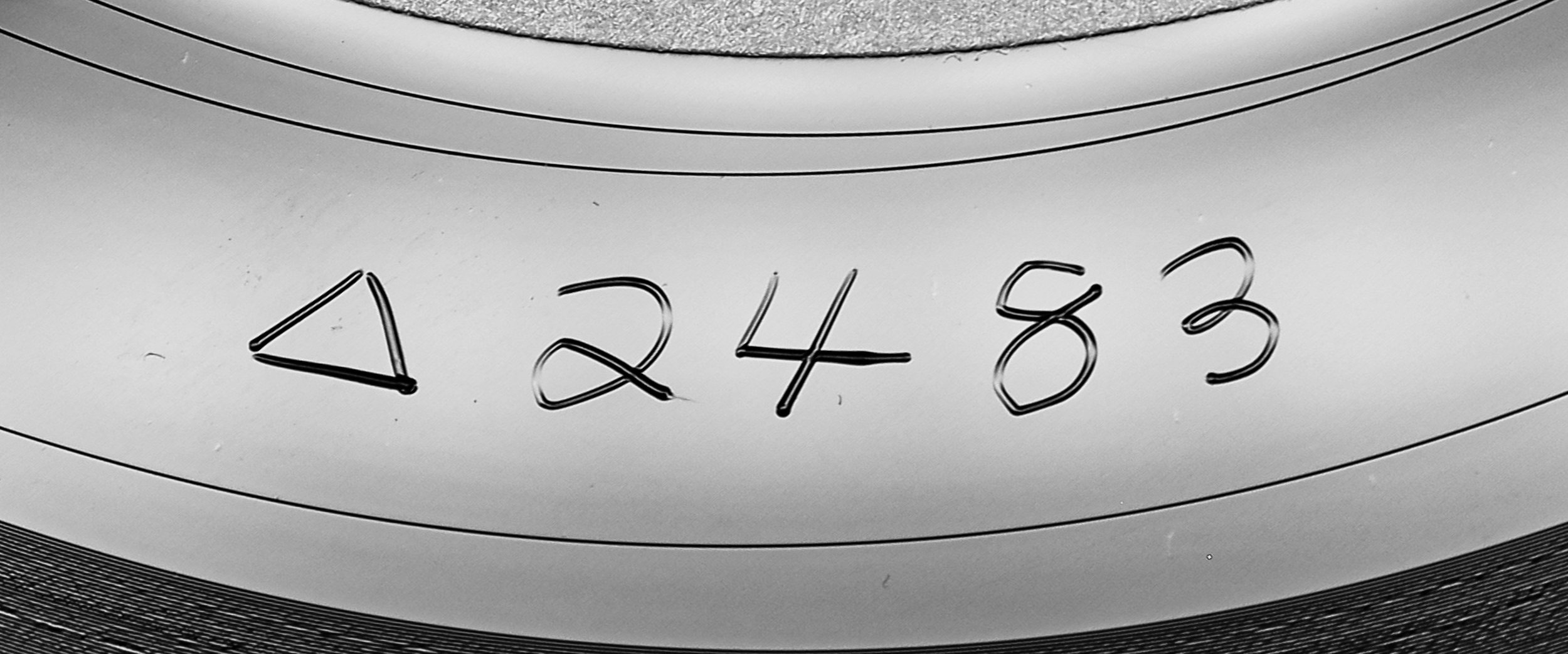

SLM Delta codes (Δx, Δxx, Δxxx, Δxxxx; also -X)

Like Monarch, SLM used delta job codes to track its operations. Of note, maybe, is that SLM head Richard Doss had previously worked at Monarch.

Some of the very first SLM jobs were new titles for Contemporary. The relationship persisted until the Fantasy sale in 1984; the Delta codes for Contemporary jobs spanned from the single digits up to the 5000s.

Recycled SLM codes

SLM delta codes were specific to each side, but not to each lacquer. To explain: if a pre-existing SLM side pressed through all of its metal and needed a new lacquer cut to refill supply, the new lacquer would bear the same delta code as the previous one. One example is below, with two lacquer generations of C3552 Benny Golson’s New York Scene:

We should not confuse this with the creation of -A and non-A lacquer pairs, which were tandem versions of the same cuts and thus not given different D numbers. What we’re seeing above with New York Scene is two separate lacquer generations cut at different times.

Recycling these codes was very rare in the context of Contemporary because SLM only plated five low years for them. I know of three examples including the one above. So we can generally consider delta codes as stand-ins for specific lacquers (or tandem -A and non-A lacquer pairs), understanding we can do so because we’re examining a statistically limited timeframe.

(We’ll touch on ‘A’ lacquers in a moment.)

Other SLM indicators

Plus signs SLM was known for a plot-and-dot system which used two “plus signs” etched in the runouts to track mother and stamper for each side. It would have been fun to decipher that system but I’ve never seen it on Contemporary’s SLM stuff. The plus signs are usually there but never plotted. Not sure what to make of it.

“CBS-SM” You’ll find on some ≤1981 lacquers an inscribed CBS-SM which seems like SLM confirming the metal’s destination with surprising clarity. Later represses done at Wakefield might still sport the extant CBS-SM.

Runouts & Handwriting: John Koenig

I’m not a handwriting expert. Still, patterns are patterns, and where etching styles obviously recur we should take notice. For example, examine the etched script on Art Pepper’s At the Village Vanguard sides, the jackets for which all credit John Koenig with Disc Mastering, and compare it against some other 1979 new titles:

S7642 Thursday Night at the Village Vanguard

S7644 Saturday Night at the Village Vanguard

S7637 Hampton Hawes at the Piano

S7641 Something for Lester

Meanwhile this style also appears on several replacement/reissue cuts. Some have SLM codes putting them in 1979-80, but others are (theoretically, earlier) CBS processing jobs. Meaning this style was not the hand of a plating engineer; it was someone manning the lathe.

S7569 (CBS-processed) Tomorrow is the Question!

S7530 (CBS-processed) Way Out West

C3552 (SLM Δ50) Benny Golson's New York Scene

S7555 (SLM Δ90) Jazz Giant

There’s one more large crumb to connect this hand “writing” to John Koenig.

A 2015 video previewing the (soon aborted) Analogue Productions Contemporary series showed Chad Kassem and John Koenig visiting Bernie Grundman Mastering to cut lacquers for Way Out West. The footage shows a side 2 of a yellow label stereo press spinning on the lathe as the men compare it to tape playback.

John specifies this as his cut — and you can see it’s the Wakefield expression of the LKS-34-D6 lacquer. In the runouts of which is, again, the specific hand we’ve seen many times:

Side 2 with LKS 34 D6 metal.

LKS 34 D6 lacquer string.

This feels like a solid enough connection. I’ll run with the idea these are John’s etchings.

It doesn’t mean the inverse is true. Meaning, the absence of this etching style doesn’t mean a lacquer wasn’t cut by John. Case in point, the two sides of S7639 show different styles, one John’s hand and the other side stamps. I have little doubt that John cut both of these, as with all the 1979-80 leftover recordings from his father’s final years.

S7639, Side 1 No Limit

S7639, Side 2 No Limit

It’s not just a question of etching vs. stamps. Different etching styles appear on 8481 Melrose cuts in this final era:

S7569 (CBS-processed) Tomorrow is the Question!

S7577 (SLM Δ283) At the Black Hawk Vol. 1

S7582 (SLM Δ285-x) Songs I Like to Sing!

S7527 (SLM Δ307-x) Blackstone Legacy, LP1

These look somewhat similar to one another but clearly different than John’s hand. It doesn’t mean he didn’t cut them and have the runouts etched by someone else, perhaps in plating. Or John Koenig has multiple personalities.

Or they may have simply been cut by another engineer at 8481.

Cutting location: 8481 Melrose vs. Later

The two New York Scene lacquers we saw earlier illustrate a separate concern for these SLM sides: determining cutting location. Contemporary closed the doors at 8481 Melrose in 1980 and we can loosely use lead-out pitch (which can be measured in LPI, lines per inch) to position a lacquer on one side or the other of that line.

The lathe at 8481 had a wide default pitch, whereas the mystery cutting location that Contemporary hired for 1980+ replacements and reissues had much tighter LPI, illustrated by these two lacquer generations for the same side:

Before we celebrate, note that several 8481 Melrose sides defy this wide lead-out setting. If the material was loud or dynamic or long and the cut extended too close to the center label, the pitch computer would need to override the default lead-out LPI to a tighter setting. You can see that happening in the constrained lead-out example below, where the lathe has no hope of completing a 360-degree rotation before reaching the lock groove but gets two-thirds of the way there by squeezing down the pitch:

So identifying the lathe by lead-out pitch is not 100% reliable. However, using it hand in hand with SLM codes is solid work which caps delta codes for Melrose Place cuts in the Δ350s:

Tandem ‘A’ lacquers

Starting in 1980, many Contemporary pressings exhibit ‘A’ lacquers, with the letter affixed to the lacquer D number.

‘A’ lacquers seem to be tandem-cut versions of non-A lacquers, meaning two “copies” of each lacquer were produced using tandem lathes in order to double pressing yield.

Important to note here Contemporary had just the one lathe and could not cut lacquers in tandem. So where these pairs exist, they point to cutting elsewhere 1980 or later, either Bernie Grundman @ A&M (14000 titles) or the studio cutting reissues/replacements from 1980-84.

Again: any ‘A’ lacquer (and its non-A counterpart) were NOT cut at 8481 Melrose Place.

Now, while multiple lacquer copies doubled pressing yield in theory, both didn’t always make it to press. The most likely explanation is that most titles didn’t sell enough copies by 1984 to spend through all the metal for one master before needing to tap into the other’s supply.

However, we see a couple examples where both tandem copies appear in print. Take these two pressings of Art Pepper’s Smack Up, one the 1982 Japanese delivery from Warner Pioneer and the other the 1984 OJC released after the Contemporary sale to Fantasy. Both use 1982 US cuts, but on side 1, Warner uses a non-A lacquer and OJC the ‘A’ counterpart. Notice the SLM delta code Δ2290 assigned to both.

Who cut reissues from 1980 to 1984?

This is a big remaining question at this point. After the closing of 8481 Melrose in 1980, new titles in the 14000 series were cut by Bernie Grundman at A&M. But who cut all the replacements and reissues in this period?

Long story short, I don’t know. My original instinct was that Bernie cut them, because why wouldn’t he? The problem is, all the evidence points away from him.

Consider 14006 Relaxin’ at Camarillo, the single 14000 series title that doesn’t name Bernie on the jacket as mastering engineer (it names nobody). Its lead-out pitch is specifically different than the pitch on Bernie’s lathe(s) at the time:

Consider also etching styles here, the classic Bern hand versus the subtly different script seen on Relaxin’.

THIS is Bernie

This is not

Every single BG-credited cut in the 14000 series has the wide lead-outs and typical Bernie script style as shown above (and as seen throughout the past 55 years of his cuts). Relaxin’ simply doesn’t have those, and looks distinctly like the replacement/reissue lacquers cut between 1980 and 1984.

So who cut the reissues? Again, I don’t know. But the runouts suggest it wasn’t Bernie.

1979-1980 NEW TITLES (S7600 series)

Lacquers cut @ Contemporary

New lacquers processed @ SLM

Five new titles dropped in early 1979, as John Koenig finalized leftover sessions from his father’s tenure. These show very early SLM codes and their runouts provide visual ammo for deciphering other lacquers in this timeframe.

In this final 1979-80 stretch for the cutting room at 8481 Melrose, we see SLM codes topping in the Δ350s and a default wide-pitch lead-out (with some allowance for the width to be constrained by the available deadwax).

The vast majority of these had etched lacquer strings, some with the John Koenig script discussed above, but at least one (pictured below) uses the large stamps previously seen in the 1975-77 CBS timeframe.

New Title, S7637 (1979) Hampton Hawes at the Piano

New Title, S7639 (1979) No Limit

1979-1980

REPLACEMENTS & REISSUES

Lacquers cut @ Contemporary

New lacquers processed @ SLM

I’m adding the word reissue into the mix. Under John Koenig’s leadership we see a conscious effort to restore into print some titles which had lapsed out of the market, thus the “A Contemporary Classic Now Available Again” hype sticker. This sticker was liberally applied, though, and stuck on some titles which had been steadily in print for decades. Demand for those in-print popular titles was satiated by replacement lacquers as needed.

Replacement, S7555 S1 (Δ90) Jazz Giant

Reissue, S7582 S1 (Δ285-X) Songs I Like to Sing!

Reissue, S7526 S2 (Δ286-X) Landslide

Replacement, S7589 S1 (Δ305) For Real!

1980-1981 NEW TITLES (14000 series)

All but 14006 cut by Bernie Grundman @ A&M

Tandem ‘A’ lacquers; parallel SLM and CBS plating

SLM intook most Contemporary lacquers after 1978, with the remainder sent directly to CBS.

In the CBS section above I showed two such lacquers, 1980 titles which showed CBS processing. It seems like the 14000 series titles were cut in tandem by Bernie Grundman and one “copy” of each cut sent to each facility. Meaning: one copy of a lacquer went straight to CBS to be processed and plated and pressed, while the other went into the SLM plating pipeline.

Case in point, the examples below, tandem lacquers LKS 367 D1 and LKS 367 D1A:

LKS 367 D1 (CBS processed) Peaceful Heart, Gentle Spirit

LKS 367 D1A (SLM processed) Peaceful Heart, Gentle Spirit

1980-1981 REPLACEMENTS & REISSUES

New lacquers processed @ SLM.

First pressings made @ CBS Santa Maria.

To isolate non-Contemporary cuts in this 1980-81 window (the ceiling defined as the closing of CBS Santa Maria in late 1981) requires looking at the SLM codes and lead-out pitch.

Any delta code between 340 and 900 that also has tight pitch lead-out points to 1) cutting by the post-8481 replacement/reissue studio and 2) first deliveries of these cuts pressed at CBS Santa Maria.

C3515 (SLM Δ813) This is Hampton Hawes

S7583 (SLM Δ831) Teddy's Ready!

That takes us to late 1981. To fully dissect the runouts of the post-8481 Melrose Place era, we need to look forward to Contemporary’s next pressing partner, Wakefield.

Wakefield Mfg. (1981-84)

CBS Santa Maria shut down operations in late 1981. Contemporary faced no shortage of options in Southern California, but for the first time they actually looked out of state, to Wakefield Manufacturing in Phoenix. WM was known for high quality output, with much of its work in this period made on lightly translucent Quiex audiophile vinyl. On the plating team was eventual QRP plant manager Gary Salstrom (now General Manager at Paramount Pressing & Plating in Denver).

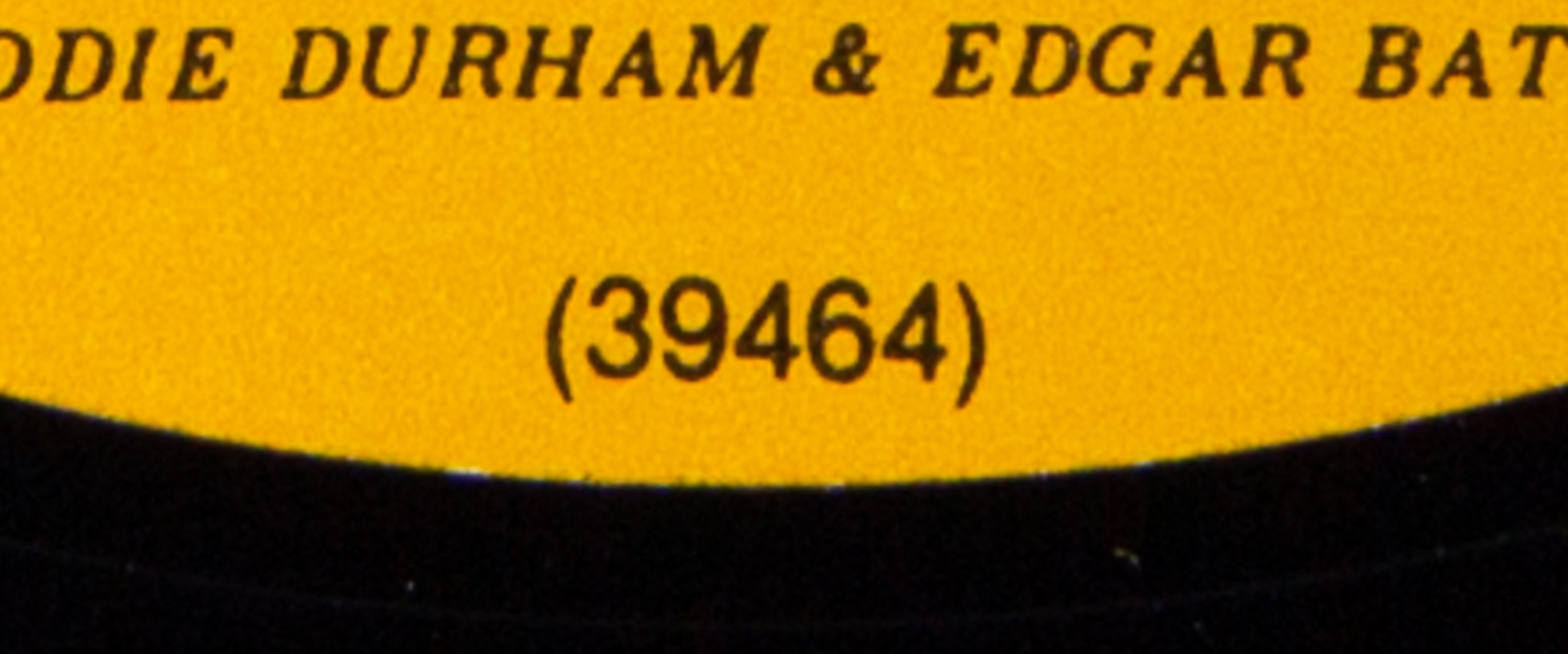

Wakefield job codes (xxxxx-A / -B)

Wakefield didn’t process lacquers for Contemporary, but certainly did replating work on metal sourced from SLM or CBS. We can see their hand in the job codes added to the runouts.

Contemporary’s Wakefield jobs are in the 39000-42000 range and span from 1981 to 1983.

S7543 Pal Joey SLM Δ933 (late 1981 cuts)

S7555 Jazz Giant SLM Δ90 (1979-80 cuts)

S7548 Gigi SLM Δ1971 (1982 cuts)

S7574 Carl's Blues SLM Δ4500 (1983 cuts)

These codes were actually printed on a few center labels, for example S7528 Music for Lighthousekeeping below.

This was isolated, however, seen only on a few reissues in the late 1981/early 1982 period. The vast majority of Wakefield pressings, including new titles, are not this obviously labeled.

Other Wakefield etchings

Wakefield etched some additional trackers, such as the title catalog number assigned by the label and metal indicators in the form of SM#x and #x.

Catalog number (Side 1) S7577 at the Black Hawk Vol. 1

Catalog number (Side 2) S7555 Jazz Giant

SM #x (metal indicator)

#x (metal indicator)

1981-1984 WAKEFIELD REPLATES

OLD Metal from CBS & SLM

When it closed in late 1981, CBS Santa Maria sent any extant Contemporary metal to Wakefield. When a metal part was subsequently needed for a new pressing run, Wakefield scratched their own annotations into its runouts before re-using or re-plating it.

Simultaneously, SLM assigned Wakefield as the new destination for any new plates generated off older metal masters (assuming those older masters indeed sat with SLM).

S7532 (CBS to Wakefield replate) (previously pressed @ CBS-SM) Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section

S7577 (SLM to Wakefield replate) (previously pressed @ CBS-SM) at the Black Hawk Vol. 1

Case in point, see two expressions of LKL 12-161 D6, one showing only SLM etchings and a later version anointed with Wakefield codes:

SLM Δ50 (1979-81 press) C3552 New York Scene

SLM Δ50 (1982-84 press) C3552 New York Scene

1981-1984 WAKEFIELD ETCHINGS

NEW LACQUERS (metal received from SLM)

Contemporary’s lacquer processing remained with SLM. Remember Wakefield was a full state away, so it would have been a leap for Contemporary to ship lacquers there with SLM just down the road.

So SLM did initial plating on all new lacquers and sent that metal to Wakefield, presumably in the form of mothers (based on the fact that Wakefield’s codes are noninverted and don’t appear sloppy like they were written backwards).

By this point, late 1981, SLM’s delta codes had crossed into the Δ800s. As stated earlier, any SLM jobs originally intended for pressing at CBS Santa Maria had job codes under Δ900.

There appears to be a small gap in codes where this pressing plant transition occurs, so job codes over Δ900 invariably point to lacquers cut after Contemporary moved pressing to Wakefield.

S7543 Pal Joey, side 2 SLM Δ933-X / Wakefield 39326-B ~ late 1981 cut

S7548 Gigi, side 1 SLM Δ1971 / Wakefield 40478-A 1982 cut

The Wakefield relationship, operating in parallel with SLM, takes us to the end of Koenig Contemporary in 1984.