Reading Runouts:

Cutting, Plating & Timing

Between the engineer’s lathe and the vinyl press sit several manufacturing steps. While trying to keep this plating process organized and consistent, the facilities that manage it often leave visual evidence behind— evidence which arrives to us in the runouts of records.

You’ve seen these. A pressing plant’s custom stamp; the barely-visible inscriptions which must have meant something to somebody; the numbered codes that helped file that metal part onto some high shelf way back whenever. These runouts keep press parts organized, and assure that stampers get matched with the correct side labels (which are usually printed with a matching code for this purpose).

I like to view the runouts like the stamp pages in a passport, showing each plant its metal passed through before arriving at the press. In line with that, Contemporary’s runouts prove fruitful and dependable as evidence of the people and partners involved.

Still, understanding this data requires an acquaintance with history before attempting to read it. So we have to discuss it all in tandem, with visual examples balanced against historical context.

A word of caution… this page is a bit of a wild ride without guardrails. It’s without doubt the most important collection of research on this site, but it’s less spoonfeeding and more me laying out the buffet. The answer you’re seeking is probably somewhere here, but it might take an ounce of patience to find it.

Part 1

00. Plating Basics

01. RCA Hollywood

Part 2

02. Monarch Rec. Mfg. Co.

03. CBS Santa Maria

04. Sheffield Lab Matrix

05. Wakefield Mfg.

Plating Basics

Let’s get the bare fundamentals out of the way.

the Lacquer

The mastering engineer inscribes musical grooves into a lacquer, an aluminum disk coated with nitrocellulose. The product of this step is playable but also extremely fragile and requires prompt processing. So the finished lacquer is sent to a plating facility, where it is silvered then electroplated with metal across its entire playing surface.

the Metal Master

Once done, that metal layer is pulled away from the lacquer, leaving a negative impression of the original grooves. This metal part becomes the metal master.

The lacquer is deemed unusable and theoretically discarded after it’s birthed the metal master… however, as I’ll show later, Contemporary seems to have had its lacquers returned to them and stored.

the Mothers

In the traditional three-step plating process, the metal master is plated and from it pulled a mother. Generally several mothers will be pulled from the metal master, perhaps all at once or periodically as new parts are needed to sustain pressing demand. The number of mothers per father is not a universal truth; it seems to depend on the specific plant and how far they choose to push the master before they deem it too worn.

The mother is a negative of the negative and has the same grooves as the original lacquer. This makes it playable by cartridge, so plants will often use the mother to test for any defects/ticks/scratches introduced in plating. Sometimes they physically attempt to correct these; other times a defect requires moving backwards in the process to replace the mother or have the engineer re-cut the lacquer.

the Stampers

Once deemed worthy, the mother is plated and from it pulled a stamper. Like the master to mother translation, several stampers will be pulled from a single mother, with specific number dependent on the plant.

The stampers’ job is self-explanatory — they’re used to stamp records. As a negative of the original lacquer, stampers are (after some additional physical steps) loaded into the vinyl press and used to create records.

Source: Basic Disc Mastering, Third Ed. by Larry Boden.

Photo & illustration by Dave Hernandez.

At any one of the steps can the disc have its runouts marked. Still, the most common place is at the beginning, in the lacquer itself, prior to plating. In addition to any inscriptions or signatures left by the cutting engineer, the plating facility will often mark the lacquer on intake with additional numbering or labeling for their own internal use.

Sometimes these plating facility marks were machine-made and stamped, and the style of those stamps changed with time. Sometimes they featured facility-wide job codes which would rise sequentially. In cases like these, the plating marks become excellent indicators for a lacquer was processed.

Remember that lacquer processing occurs immediately after cutting. So reading runouts and dissecting plating evidence is usually our best hope for narrowing down when a lacquer was actually cut.

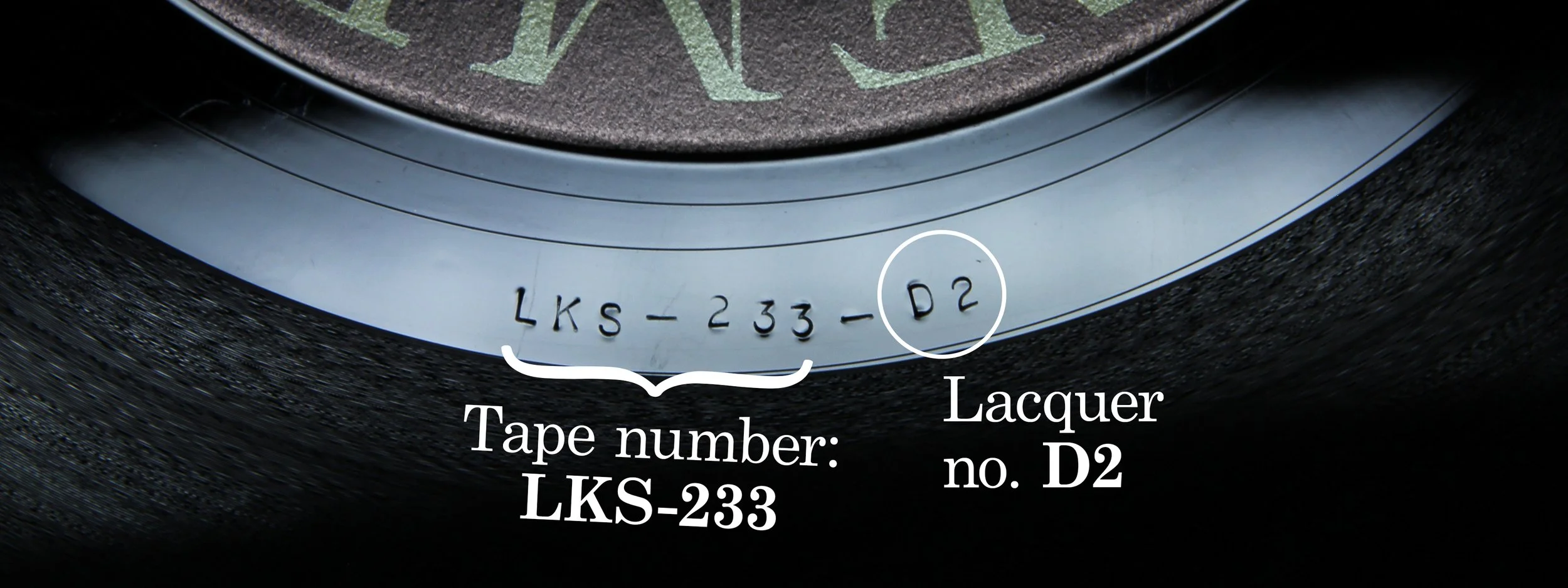

The lacquer string

I’m making up this term, I think. The lacquer string is the unique identifier assigned to each lacquer.

Every Contemporary lacquer cut under the Koenig ownership from 1954 to 1984 had the same structure for these strings as they appeared in the runouts. Like this:

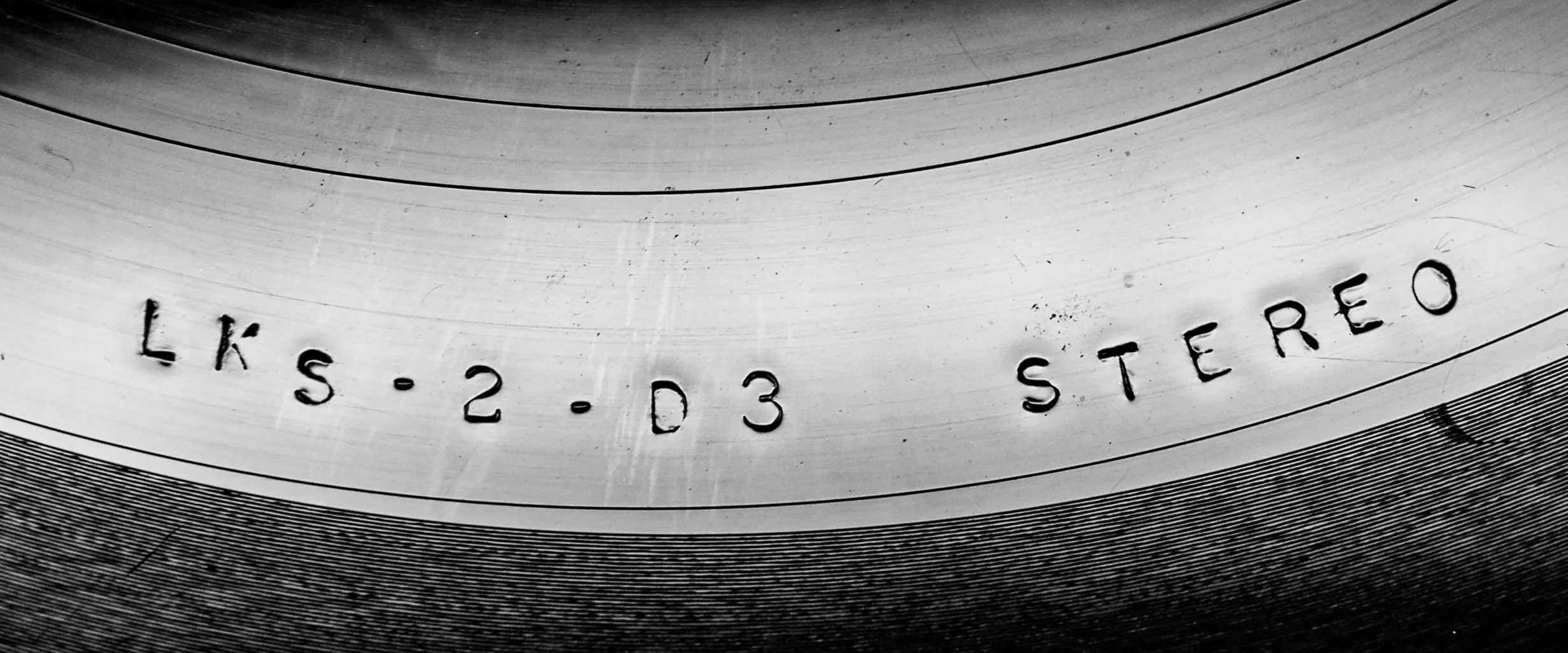

Invariably, Contemporary lacquers feature:

The internal master tape number given to each side, starting with either LKL (for mono) or LKS (for stereo).

The lacquer number, Dx. The first attempt at cutting a side would be given D1, and further re-cuts would go up sequentially from there. Two sides often had different lacquer numbers.

Mono tapes for 12-inch LP, whether single-track or stereo two-track intended for fold-down, were assigned a number LKL-12-x. The 12 was added with the first Koenig 12-inchers to distinguish them from earlier 10" LPs (which were all mono). Those 10" releases read simply LKL-x.

Stereo tapes would be assigned LKS-x.

Note that by 1959, sessions were regularly recorded in two-track only, with one set of master tapes assigned separate tape identifiers for mono and stereo. See tape numbers and the 50-50 Line.

Who stamps or etches the runouts?

While the cutting engineer was likely responsible for correctly assigning the lacquer string, the style in which they appear in the runouts were sometimes a symptom of the plating plant.

To understand why, consider lacquer dimensions. The lacquer is larger than the eventual record; for example, a 12-inch LP side requires a 14-inch lacquer. Those extra inches will eventually be trimmed but are there for a reason, namely to allow the cutting engineer a test cut before diving into the music.

Meanwhile — and this is the relevant takeaway here — the extra space can also be used to inscribe information. This is less tight-fingered work than scratching between runouts, so mastering engineers have often used that space to etch cut information.

The drawback being, these notes outside the playing area will be trimmed off and not pressed into the descendant metal. To preserve that outer info, then, the plating facility’s staff might be tasked with copying it to the runouts. This can be done by hand, probably by somebody who’d get really fucking good at it over time; however, many plants of yesteryear bypassed human fumbles completely and used stamp machines instead.

RCA’s Hollywood pressing plant, for example, stamped the strings for every Contemporary LP from 1954 to 1973. Contemporary’s subsequent plating partners would handle these strings differently and Contemporary’s engineers would soon began marking inside the runouts themselves.

RCA Hollywood (1954-73)

RCA had four pressing plants in North America, and each plating department used location-specific stamp styles and runout markings. We don’t need to cover them all, only Contemporary’s local partner in Hollywood.

RCA Hollywood stamp fonts

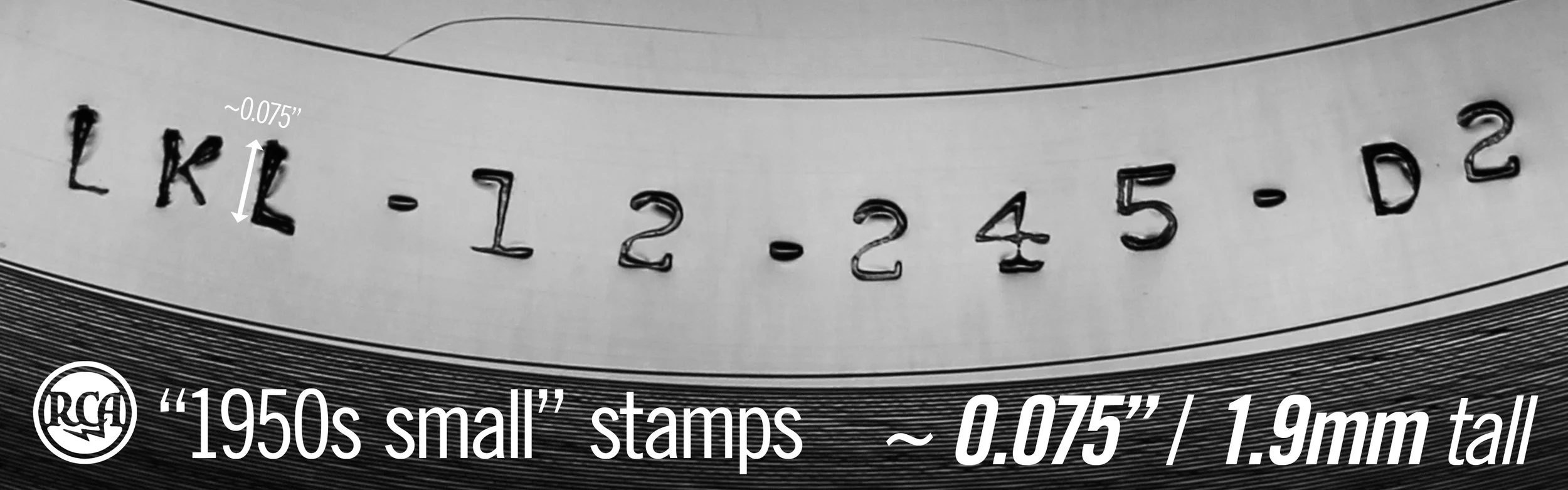

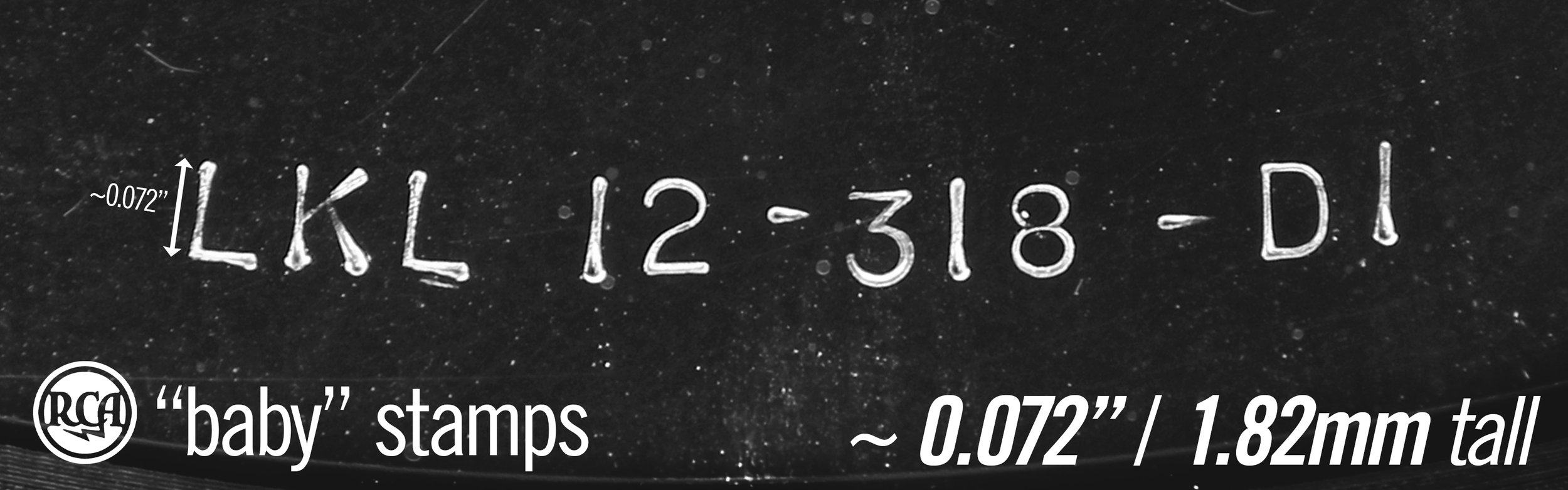

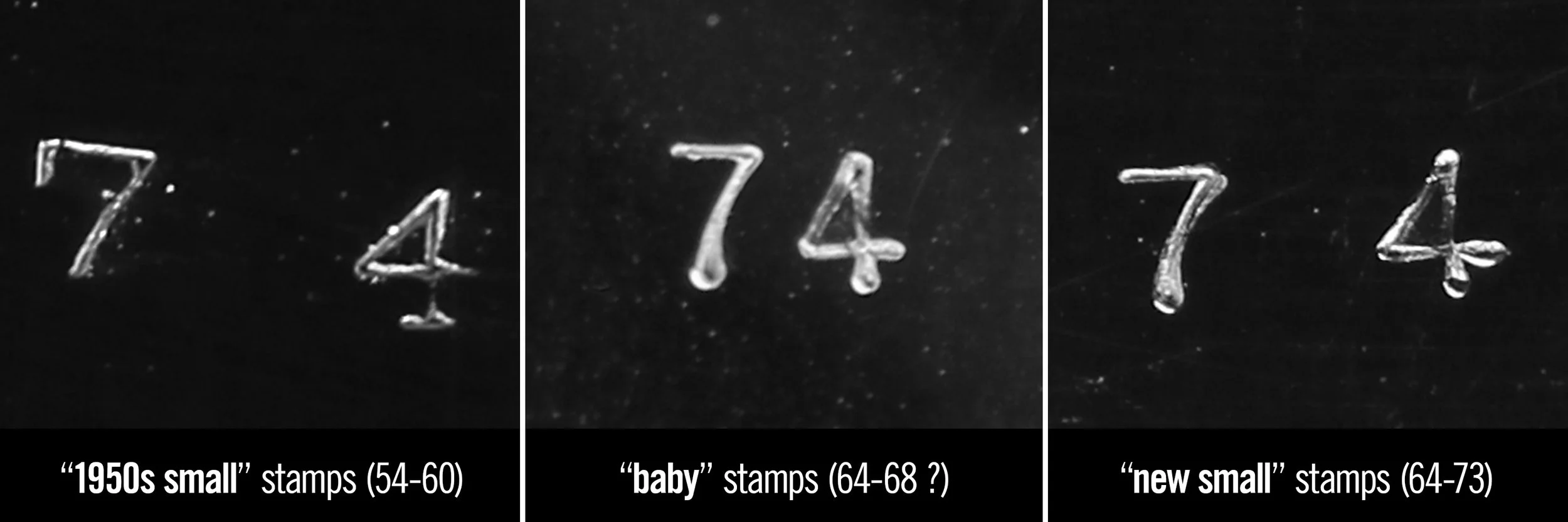

Four distinct stamp styles/fonts Contemporary’s RCA-era runouts. I don’t know if there were specific titles given to each of them by whatever stamp letter vendor or whatever. I just made up some names:

This was RCA Hollywood’s standard stamp style in the 1950s. Looking closely, these can appear slightly embossed, as if pulling the surface upwards with a heavy impression.

These larger characters supplanted the smaller ones in 1960. They’re not just larger, they’re an entirely different sans serif font pressed with a far lighter impression. Sometimes uneven. Difficult to photograph. You’re welcome.

Likely to be confused with the large stamps seen on mid-1970s cuts processed at CBS Santa Maria, these RCA large stamps are specifically ordered, with precise kerning as seen in the sample above.

One solid piece of timing evidence is the original lacquer below, stereo side 1 for S7538 Red Mitchell Quartet; its original lacquer envelope places the cut in March 1962:

These are somewhat rare. Very demure. They appear on the baby handful of new LPs that came out of CR Inc. from 1964 to 1968, however evidence suggests they were in use alongside the newly-returned “small” stamps. A separate baby handful of reissue cuts also have these stamps. Unique to this style: tight kerning between characters, specific sans-serif “1” stamp, and stamp height ~0.072 inch (measurably smaller, sorta, than ~0.075-inch stamps).

The ~0.075mm stamp reappeared around 1964, with slightly different characters and significantly different digits than its 1950s counterpart.

The “1950s small,” “new small,” and “baby” stamps can look similar at first blush, but the key is in the digits. Below shows some illuminating examples — focus on the digits 1, 2, 3, 4, and 7 below — by which to reliably separate these stamp classes:

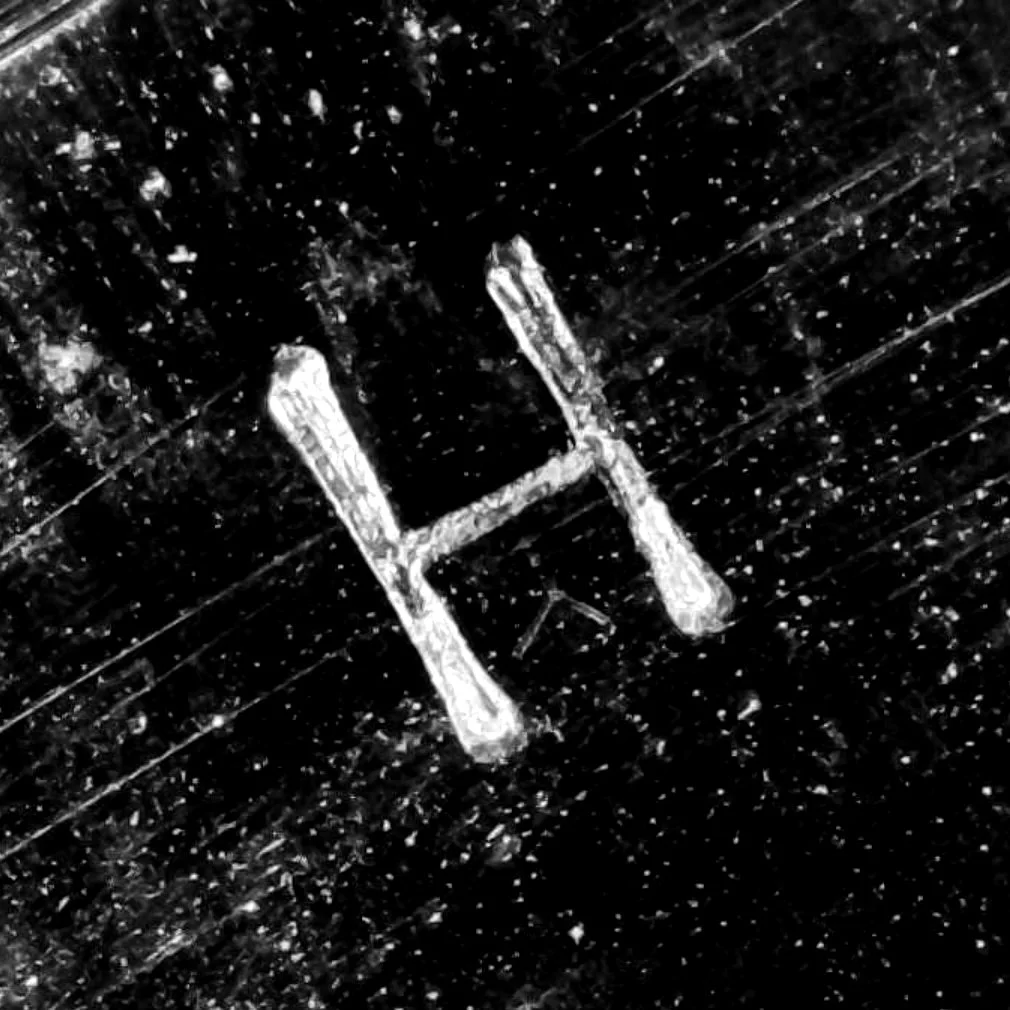

The Hollywood plating operation pressed an “H” stamp into most lacquers which came through the door. Though application of the H was standardized and measurable, it was not constant or universal.

Some of Contemporary’s earliest 12-inch lacquers from 1954 have the H; some don’t. Where I’ve seen it on 1954-55 lacquers, it was positioned close to 8:45 on the dial if you center the lacquer string at 6 o’clock. That positioning isn’t especially dependable so I’m not going to include that.

Sometime in 1955, the position locked in around 2:30 or 3. It stayed there until early 1959 then went up in smoke. It reappeared in 1961, in a new 12 o’clock position.

I’m not sure what to make of those positions, but they are pretty reliable evidence:

A second separator between these two iterations of the H stamp is its orientation to the groove direction. From 1955 to 1959, the H’s baseline would sit perpendicular to the groove; when it reappeared in 1961, that baseline was made parallel to the groove:

This H stamp was generally stamped into the lacquer itself, though I’ve seen seen at least one illuminating example of it punched into metal, and that is below.

These are expressions of the same lacquer, LKL.12.127.D4, the first with no H stamp and the second with the H stamp. Meaning the original lacquer didn’t have the H.

The stamp style alone puts a ceiling on this lacquer at 1960. Factoring in that it has no H stamp, you’re looking more specifically at 1959-60. It’s also important to consider specific context for the title; the concentric lead-out indicates a 1958+ cut but I also know the concentric side 1/D3 preceded this one to market. So the 1959-60 timeframe makes plenty of sense for D4.

I’d guess the expression above with no ‘H’ stamp is an earlier run, with the ‘H’ stamp being added to the metal sometime 1961+. Supporting this is the H stamp’s position at 12 o’clock and its parallel baseline; this is how it usually appeared in new lacquers after 1961.

Cutting location:

Eccentric vs. Concentric Lead-out

The eccentric lead-out was standard practice on 78s and early LPs, its dramatic inward-outward movement required as a trigger for auto-stop functions on record changers. In the late 1950s, multi-format changers — among those formats being 45s with concentric lead-outs — adopted a new “velocity trip” feature which needed simple inwards movement to trigger the stop function.

I’ve written more about this in Mastering History Vol. 1. Here I’ll just touch on timing: the eccentric lead-out remained industry standard into the late 1950s then quickly disappeared from most mastering studios around 1958 or 1959.

Contemporary’s mid-late 1950s LPs were cut at Capitol Studios which used the eccentric lead-out. Then, when Contemporary built their own lathe and cutting room in 1958, they adopted the concentric lead-out. Absent any inscriptions made by either studio in the runouts, the lead-out style becomes the critical distinction between them.

So, if a 12” Contemporary lacquer has an eccentric lead-out, it was cut at Capitol. If it has a concentric lead-out, it was cut at Contemporary (up to 1980).

Collected Plating Timeline:

MONO 1955-1963

All the above covered, let’s look at MONO runouts step-by-step from 1955 to 1963.

C3517 In The Solo Spotlight

C3551 Something Else!!!!

M3569 Tomorrow is the Question!

M3588 Together Again!

M3602 Smack Up

STEREO stamps

In the first several years of the stereo era, Contemporary lacquers had STEREO denoted in the runouts alongside the LKS lacquer identifiers. This first appeared as separate characters S T E R E O in the same stamp style as the rest of the string, then as a different STEREO stamp separate and distinct from the regular identifiers:

S T E R E O Separated stamps (1958-1959)

STEREO Unified stamp (1959-1961)

The STEREO stamp disappeared in 1961. Ignoring any external causes (eg. the wider normalization of stereo LPs), this sudden absence is but another checkpoint by which to funnel lacquers into smaller windows of time.

By cross-referencing the two distinct stereo stamps (or lack of stereo stamps) against the other runout stamp styles already discussed, we can roughly date any stereo lacquer cut between 1958 and 1963:

Collected Plating Timeline:

S T E R E O 1955-1963

S7025 Peter Gunn

S7565 Some Like It Hot!

S7576 Poll Winners Three!

S7589 For Real!

S7597 Lookin' Good!

S7599 Checkmate

Sidebar: Exceptions & Oddities

A small subset of lacquers don’t exactly follow the patterns outlined above. The STEREO stamps in particular create some minor variation from the norm, as seen on the exceptions below.

S7008 Music For Lighthousekeeping Several early 1958 stereo lacquers show no stereo notation at all.

S7002 My Fair Lady Other 1958 STEREO lacquers are suffixed (rather than prefixed).

S7591 Folk Jazz STEREO stamp dropped into the middle of the string, and the other stamps mixed "big" and "1950s" styles.

S7597 Lookin' Good! Some of the strings c. 1961 are stamped "upside down," ie. with the letters baseline on the label side. Kind of futzes with the "6 o'clock" orientation I've been assigning to the string on RCA plates.

There are undoubtedly more exceptions around, but RCA’s stamping patterns are surprisingly consistent when viewed as a whole. Instinctively I expect American manufacturing to be prone to some degree of omission and disorder, but RCA’s style was really quite buttoned-up.

1964-1968 NEW TITLES

“Baby” Stamp Lacquers

Between 1963 and 64 the “big” stamps were replaced with multiple styles.

Let’s run down the “Baby” stamp font, which showed up on new titles in 1964.

M12051 San Francisco Bay Blues, mono rec. 1963, released ~Apr. 1964

S8013 Divertimento Nos. I & II..., stereo released Spring 1964

M3615 The Newborn Touch, mono rec. Apr. 1964, released Jan. 1966

S7616 Here and Now, stereo Side 1/D1 rec. May 1965, released Jan. 1966

1964-1968 REPLACEMENT LACQUERS

“Baby” Stamps

A separate group of replacement lacquers, cut to replenish the pressing metal for old in-print titles, were stamped with the “baby” style in this era. Two below.

M3530 Way Out West

S7551 Something Else!!!!

MIXED STAMPS 1964-1968

“Baby” & “New Small”

As alluded to in the graphics, these “baby” stamps were only applied to a subset of lacquers in this period. Consider The Green Leaves of Summer, recorded in February 1964 and quickly turned around for release by April 1964 (that’s what we in the biz call a helpfully tight research timeframe).

Off the original mono white label promo, side 1 shows “baby” stamps, but side 2 employs the distinctly different “new small” stamp style.

The same mix of “baby” and “new small” stamps are found on Here and Now (recorded 1965) and Firebirds (1967). Meaning the “baby” stamps and “new small” stamps were likely in concurrent use for several years. Best guess, 1968.

M3614 / S1 The Green Leaves of Summer Side 1/D2 ("Baby" stamps)

M3614 / S2 The Green Leaves of Summer Side 2/D1 ("New Small" stamps)

S7617 / S1 Firebirds Side 1/D2 ("New Small" stamps)

S7617 / S2 Firebirds Side 2/D2 ("Baby" stamps)

1964-1973 NEW TITLES

& REPLACEMENT LACQUERS

with “New Small” Stamps

The “New Small” stamps are, in the grand scheme of things, the far more common style, which stayed in use into the 1970s. While these began appearing back in 1964, every new Contemporary title from 1969 to 1973 features “New Small” stamps ONLY.

Meanwhile, numerous 1950s/early 60s titles wore through their metal by the late 1960s, creating the need for dozens of replacement lacquers in the 1964-73 stretch, and most of these new cuts are identifiable by the “New Small” stamps.

New Title S7616 (1966) Here and Now

New Title S7619 (1969) The Fox

New Title S7627/8 (1971) Blackstone Legacy

New Title S7631 (1973) I'm All Smiles

Replacement S7028 Jazz Giant, Side 2

Replacement S7535 The Poll Winners, Side 2

This period also saw the first stereo release of several 1950s titles who’d only seen market in mono. (One such title is S7549 The Arrival of Victor Feldman, which is discussed in more detail on its dedicated page.)

Here are two actual lacquers for belated stereo titles, along with their dated envelopes showing 1968 and 1972:

S7545 All Night Session, Vol. 1, STEREO Lacquer, side 2, cut Nov. 20 1968

S7538 Red Mitchell Quartet, STEREO Lacquer, side 2, cut Jun. 12, 1972

You might be confused seeing actual production lacquers here. Yes, lacquers are generally considered unusable after being plated. My understanding has always been that they are discarded after being plated.

Many of Contemporary’s lacquers were, however, returned to Les Koenig after processing and then stored for decades. In the early 2000s, John Koenig partnered with Classic Records founder Michael Hobson to sell them. See this video from a former Classic employee recounting this period, and below is some copy from a set of lacquers on Discogs (I corrected some spelling; bolding mine):

Les Koenig, the founder of Contemporary Records was known to save everything and in this case fortuitously. The Contemporary Records Lacquers listed here come directly from the stash of things left over when Contemporary was sold to Fantasy Records in 1984. The lacquers were kept in their original sleeves (date stamped) after processing which produced the masters and stored in temperature controlled storage until they were obtained by TheMusic.com. The original 14" discs have been professionally trimmed to 12" discs which allow these super rarities to be played on a normal turntable and packaged in new sleeves that include the original dated sleeves to provide additional authenticity.

So these are the actual lacquers cut at 8481 Melrose. I doubt there’s a person on earth more excited to hold just one of these, but like Gimli leaving Lothlorien with golden hairs in his pocket, I feel lucky to have discovered three.

It's a Transco lacquer...

from 1968.